Good concept, poorly executed.

... View MoreThis is a tender, generous movie that likes its characters and presents them as real people, full of flaws and strengths.

... View MoreIt’s an especially fun movie from a director and cast who are clearly having a good time allowing themselves to let loose.

... View MoreClever, believable, and super fun to watch. It totally has replay value.

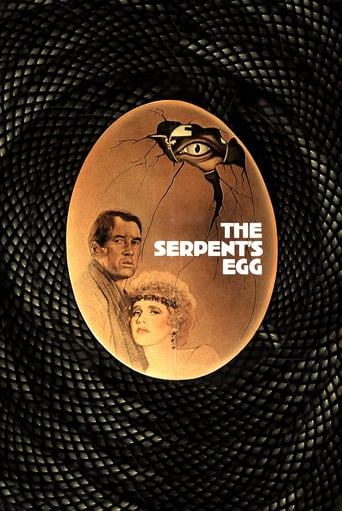

... View MoreWhile not a masterpiece, this is also far from the mess most critics took it for. An intelligent failure (or modest success) Bergman looks at Germany in the 20s as laying the groundwork for Hitler and the Nazis. Liv Ullman is terrific, as always. And if David Carradine is only good, not great, he certainly didn't deserve the critical attacks he received. The nature of his character is a man so locked in passivity as to be enigmatic. You might not like that kind of character, but it's certainly not the actor's fault for carrying it out well! Yes, some of it is slow, and some a bit obvious, but those charges could also be leveled against some Bergman films labeled masterpieces. As a cautionary tale of where we were once before, and could end up again, I've certainly seen far worse. It has some truly chilling moments. And I think seeing it again may reveal even more

... View MoreIt might really be crazy, but seems like this is one of the Bergman movies that actually did not get a high rating here. And it is crazy (for me), because this is one of his movies that I really enjoyed (though that may be a poor choice of word). It really is out there, but still coherent in its storytelling, so that you can follow it, but be amazed by the direction it takes.And while it would be difficult for me to explain its appeal and/or the plot to you (even if I had put spoilers in this, which I'm not going to do!), I can tell you that it is really gripping. Carradine might be one of the reasons for this, but not the only one. I still wouldn't know if I could recommend this to a first time Bergman viewer ... but then again, which of his movies could that be?

... View MoreIf you're never watched a film directed by Ingmar Bergman and decides to do it by watching "The Serpent's Egg", it might be a great choice for you but it will you make you hate all of his brilliant masterpieces. My perception of this film is very awkward, considering that I've watched ten of his films (including "Persona", "Wild Strawberries" and "Fanny and Alexander"), all of them magnificent, but then he comes with an American project which is very difficult to relate with since it is different than anything the Swedish master ever done before. It is faster than his previous classics, not much philosophical or methaporical, and instead it's quite meaningless for the most of its entirely until we reach the conclusion (and even faster than his other films it is tiresome at parts). Bergman is present in the beautiful cinematography by Sven Nykvist and the opening titles, a trade mark that Woody Allen used to present his films.The story of a American trapezist (David Carradine) in German investigating the reasons behind his brother suicide, during Weimar Republic's inflation crisis of 1923, might be a excellent material for a talented director/writer like Bergman but here, in his way of trying to built a suspense, create horror and disgust in our eyes something got lost in the middle. A better construction of characters or make them interesting in some way, anything. The historical background is very interesting but these characters are so driven by the automatic pilot that gets very difficult to really feel something for them and we should felt something for them. After all, they lived during troubled times, no jobs to find, no food to eat to the point of eating horse meat (yes, one was killed off-screen but the corpse's presented in the film), and there's brutality here and there (in one of the most violent moments a Nazi officer beats a Jewsih cabaret owner by smashing his head on a table. Bergman is a master in not showing us the event, we can only hear the head hitting something hard and we as audience get very uncomfortable, feeling this guy pain). If the performances of Liv Ullmann and David Carradine keeps going like a switcher from good and bad each time they appear and disappear off the screen, James Whitmore in just one scene gives a memorable moment playing a priest. Some of the supporting roles were more interesting than the main ones.The point made by the film at its conclusion was excellent but it came a little late. The idea of the seeds of 2nd World War being created in a horrific and strange experiment looked real, very believable, but Bergman could have explained more about it, it sounded something weaker than what we were expecting from what Carradine wanted to discover about the other characters deaths, which reminds of a important topic to be debated: what in the world happened to the villain? Noises on the screen of police wanting to enter in his room, then he looks into sort of a mirror, then collapses and die? I really didn't get it! And to reach the brilliance of this film is to wait and wait, and see strange and pointless scenes (the funny brothel scene is one of them), a lousy investigation made by Gert Frobe's character which includes arresting Carradine without evidences, and more.I'm sounding a little bitter about "The Serpent's Egg" but in fact I enjoyed. The bitterness comes from my fears of giving the first thumbs down in a Bergman's film while watching it. When you see the whole picture you realize that it works, it's well made, has its flaws but it's not as great as his other classics. I can't complain much about this film because the director had many problems at the time (tax evasion and things like that which made him get out of his country), and a director must live of his films, he needs to write and direct, and this was a nice work for him, he made the best of what was available to do for another kind of audience. Of course, when you see Bergman + Carradine + Ullmann + Dino DeLaurentiis as producer you really want to see a spectacle of film and not a minor work, almost forgettable. The potential for being great was there at everyone's hands but it's good anyway. 7/10

... View MoreThe design, locations, photography and minor character actors all are excellent. Ullman seems unsure of what she is doing and Carradine just wanders and when he speaks it's unconvincing.The real problem is the script as Bergman made an elementary scriptwriting error, the sort of basic thing that is criticized at a first draft stage: the protagonist is not interesting and does not change but seeks information and so he goes from place to place all documenting the sordid life in Berlin in 1923 and making portentious allusions to Nazism, but as such he has little or no dramatic action until the end when he and the audience are told exactly why and what is going on. In a book that structure might have worked but not in film.

... View More