Most undeservingly overhyped movie of all time??

... View MoreDreadfully Boring

... View MoreBlending excellent reporting and strong storytelling, this is a disturbing film truly stranger than fiction

... View MoreI enjoyed watching this film and would recommend other to give it a try , (as I am) but this movie, although enjoyable to watch due to the better than average acting fails to add anything new to its storyline that is all too familiar to these types of movies.

... View MoreI have watched this movie several times.I read Ayn Rand's four major works the first time before I was 16 years old = "We the Living" 1936, "Anthem" 1938, "The Fountainhead" 1943 and "Atlas Shrugged" 1957. I have read these four books several times. Actually I have read "Atlas Shrugged" at least twelve times. I wrote a term paper in my second semester at the university entitled "The Abstract Themes In Ayn Rand's Novels." A research paper presented in partial fulfillment of requirements in English Composition 113 submitted November 14, 1966. My grade was an "A." Yes, I earned a bachelor of science in business at the third largest accredited university in Oklahoma.It is my opinion that Ayn Rand was a genius in Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein's class. Ayn Rand was a philosopher. Her works listed above state her philosophy. I think her philosophy of "Objectivism" is the best philosophy and incorporates the principles of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. I do disagree with Ayn Rand's position as an atheist. I think her position as an atheist was influenced too much by the acts, actions and works of "men" in their creation of religion. My faith in GOD and his SON Jesus is total.I think the movie "The Passion of Ayn Rand" is well done and reflects the powerful emotions involved between the four individuals = Ayn Rand, Frank O'Connor, Nathaniel Branden and Barbara Branden.I am 41 years younger than Ayn Rand. I would have loved to have been in her life as her lover and intellectual compatriot.I can relate directly to Ayn Rand. In many ways she and I are a lot alike. From 1993 through 2010 the four significant Ladies in my life are each and every one 24 years younger than me.For me in my life I blend the philosophies of "Atlas Shrugged," 1957 by Ayn Rand and "Stranger in a Strange Land," 1961 by Robert A. Heinlein. Heinlein has stated that his book "Stranger in a Strange Land" is entirely a work of fiction. To those who revel in attacking Ayn Rand I can say only "Look into your own life and spirit to see if you can find any fulfillment." I find fulfillment when I look into my own life and spirit. I believe that Ayn Rand found fulfillment in her life and spirit.I recommend the movie "The Passion of Ayn Rand."I have watched the first two "Atlas Shrugged" movies several times. I think they are well done. I will see the third "Atlas Shrugged" movie when I can buy it on DVD. I do not go to movie theaters or use any movie services.

... View MoreBelieve me, I'm not kidding about how silly/scary some of these sessions could be, even out in the Hinterland. In the movie, they show a young woman, in front of Rand and Nathaniel Branden (Eric Stoltz), coming to tears for not having the correct interpretation of some behavioral peccadillo. It reminds you of a party-loyalty session on the collective farms in Russia and China. But the story is largely autobiographical for Barbara Branden. We see a very important part of Rand's life, Rand's husband, Frank O'Connor (Peter Fonda), as well as Barbara and Nathaniel. The plot focuses a lot on the relationships among them. It starts with Barbara and Nathaniel coming to meet Ayn Rand at her home in California... after Nathaniel had written a most perceptive letter to Rand when he had read her book, The Fountainhead. Ayn and Nathaniel hit it off at first syllogism, then, in a few years, start "getting it on" above and beyond the call of reason.

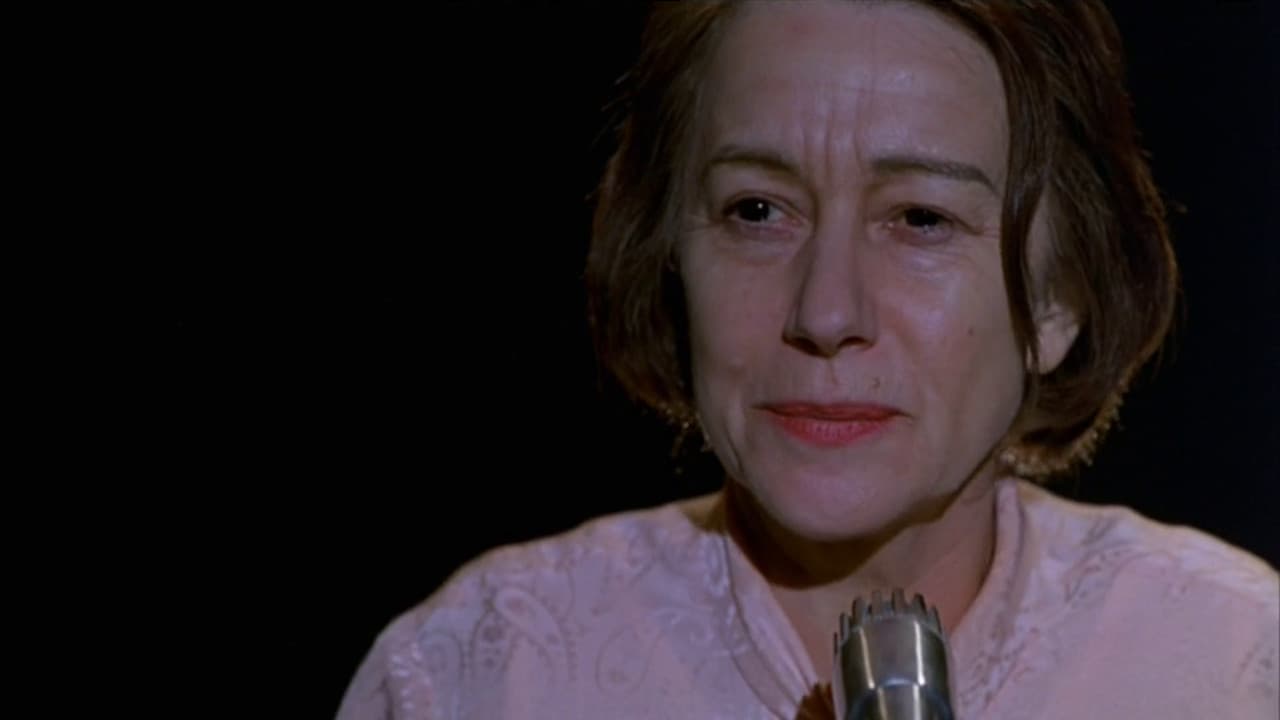

... View MoreThis dramatization of about 17 years in the mid-life of novelist Ayn Rand focuses on her intimate relationship with one of her much younger disciples, one Nathaniel Blumenthal, who changed his last name to Branden (get it? – bRANDen) after establishing a platonic friendship with the author. Eventually the relationship evolved into a love affair with the full if resentful knowledge of their mutual spouses. Although the heart of the film is the love relationship we are also introduced to the social circle of the controversial Rand whose novels featured larger-than-life heroes whose glaring individuality and egoism pit them against the common mass, or "second handers" as Rand called them; she elevated personal selfishness to a high ethical principle, and revered the capitalist way of life. The film is set during the period when Rand was writing her last mammoth novel, ATLAS SHRUGGED, which she believed would rock the world and spark a revolution of human creativity and a rebirth of individualism and entrepreneurial, creative spirit. When it became a mere best seller she was shattered and in her demoralized state allowed the young Blumenthal to influence her next career move by founding the Objectivist movement which carried her message in the form of a periodic newsletter and public meetings. Through the device of capturing snatches of conversation at dinners and small meetings as well as question-and-answer sessions at public gatherings, the film takes the time to explore the mind-set of the Rand followers, including the ugly confrontations within the innermost circle as members are emotionally humiliated for not uttering the correct Objectivist formulations in deadly group meetings in Rand's smoke-filled living room. The cult atmosphere is well captured. But the "passion" here is heavily on the sexual-romantic side and lacking in the arena of philosophy. The makers of this film probably felt the TV audience wouldn't sit still for too much cerebral content so some may wonder why people felt so strongly about Rand that they would attach themselves to her the way her followers did.But the real power in this TV movie comes across in the four central performances by Helen Mirren as Ayn Rand, Peter Fonda as her passive, dispirited, alcoholic husband, the always excellent Eric Stolz as "Branden" and Julie Delpy as his long-suffering wife. Each of these excellent actors has mastered the art of "less is more" in conveying depth of emotion with a minimum of hamminess and take the viewer inside the cult mentality. Rand could easily have been depicted as a monster but Mirren and the screenwriters take care to show us her vulnerable side. You have to admire her whether you agree with her or not. She was a tragic figure worth exploring. Her novels still sell in the hundreds of thousands of copies many decades after their initial release because there is a kernel of truth in what she wrote, something about the value of the individual and the beauty of reason. What she made of those truths is debatable.

... View MoreHaving read her book Atlas Shrugged, her Playboy interview, and subscribing to the Objectivist Newsletter for a time, I was familiar with Ayn Rand's philosophy. Let me first say that if you haven't read any of the above or her other works, this movie will not have as much meaning for you and you will not understand the significance of some parts.Since I had delved into Rand's works and was influence by them, even if only temporarily, I have to admit that this film was truly shocking in its portrayal of her. Don't get me wrong, the acting in this film with all of the characters was A+. However, the way they cast Ayn as a character, making her just as human and just as given to her emotions, was quite appalling. You see, in Ayn's work, she stresses the ideal in life, that which is held to the highest, noblest, and greatest - the achievements of the mind. She communicates this in such as way that she appears above others in society, as if sitting amongst that ideal that she preaches. Therefore any other portrayal of her ideal diminishes the viewer's perspective.**Below there are a few spoilers included to show the flaws of this film to followers of Ayn Rand's Objectivist philosophy.Strangely, this movie doesn't seem to be primarily about philosophy, but rather the torments of an extra-marital affair. The film intermingles and blends her philosophy as a backdrop to this. Granted, in her Playboy interview she does not necessarily agree that sex has to be between a married couple, however, this film almost portrays her as some of the villains she describes in her books. I suppose the most obvious reason for this is because it is an account of the non-fiction work of Barbara Branden. She was a close friend and disciple of Ayn Rand. Her husband, Nathaniel (an egotistical and sex-hungry psychologist), has an affair with Ayn Rand. The film begins to get gray here in that it doesn't fully the develop the reason for Barbara Branden's non-sexuality, which in part fosters Nathaniel's cheating on her. What is odd also and perhaps the glorified self-image of the author, is Barbara's depiction as really the only character that held truest to the Objectivist philosophy. Her love for Nathaniel seems mistaken for great admiration and respect of his intellect. Her lack of any sexual expression appears to substantiate this as she has passion for only the intellect and not the physical. Her singular defiance of Ayn's teaching is displayed with her agreement and subsequent self-immolation in allowing her husband to have an affair. Ayn and Nathaniel, on the other hand, share the same act of uncontrollability in their affections for one another. While this is displayed as logical, they ask their spouses to sacrifice themselves for their pleasure by agreeing to the affair - a big no-no in Ayn Rand's teachings. Ayn's husband, Frank, appears in a fog during most of this, washed up and washed out as he hides in his hidden anguish.But Nathaniel commits the ultimate travesty in his cheating not only on his wife but now also on Ayn herself. He begins an affair with a young woman he is counseling, while still juggling his wife and Ayn in the mix. This, of course, comes to a head and Ayn is as furious with Nathaniel as if she were his wife. She vows to destroy the man she believes she has made (what happened to the self-made hero she saw in him, the man who did not rely on others?). Strangely, Barbara once again appears noble as she defends her husband's destruction before Ayn.If I haven't explained it to you Ayn Rand's fans clearly enough, this movie is full of holes in her philosophy. I'll quote a line from Nathaniel Branden in the movie, "A philosophy should not be judged by the actions of its teachers." This statement surely applies to this film! However, I wonder just how "objective" a testament Barbara Branden gave when she wrote the book this film is based on. Because if the teachers can't follow the philosophy and remain true to it, then either the philosophy failed or the teachers never fully understood it in the first place.

... View More