Blending excellent reporting and strong storytelling, this is a disturbing film truly stranger than fiction

... View MoreThe story, direction, characters, and writing/dialogue is akin to taking a tranquilizer shot to the neck, but everything else was so well done.

... View MoreClose shines in drama with strong language, adult themes.

... View MoreOne of the film's great tricks is that, for a time, you think it will go down a rabbit hole of unrealistic glorification.

... View More...who I love it. for performances, off course, Batalov and Smoktunovsky are, always, the good choice. for the director, in same measure. for image and splendid cinematography. but, first, for human virtues in the right light. it is a film about science and love and happiness and dedication. simple, dramatic, seductive, bitter. portrait of profound solitude. and need to escape from yourself. a poem. support for reflection. about limits. about hope. about the force to escape from the circle of appearances. and the courage to assume yours limits, ideals, fights.

... View MoreOnce more my experience with Soviet films is confirmed: they are slow and too long and lack any suspense - like a bad love affair. In addition "Nine hours of a year" concerns the daily life in a laboratory of nuclear physics, which is itself a bore (= a man who, when asked how he is, tells you). There are a pile of nuclear physicists (inside joke), a number of mathematicians, an amalgamation of metallurgists and a line of spectroscopists. The main characters are a married couple of physicists, who drag out a stalemate position. Of course it is a drama to observe two (or more) immature adults, who just seem to vegetate. But not every drama qualifies as an interesting theme, and this film proves it. Still he has some value, provided that you place him in his proper context. So, are you ready? The real story is about ethics and morals! The Soviet Union justified its existence on the ground, that she eliminates the alienation of the working class. In the Leninist state the personal interest is supposed to coincide with the general interest (read: the interests of the state). In the first years there were the Subbotniks, collectives who continued working in their leisure time. Solshenytsin describes in his books a true case of a simple laborer, who is so naive that he physically works himself to death. It is morbid (= higher offer). To be fair, there is the capitalist analogy of the imperious business man, with his fits and cardiac affections - although the capitalist is still inclined to self preservation and selfish (= what the owner of a sea food store does). After Stalin the Soviet ideology began to enrich the collective moral with the formation of the unique personality. This paradox (= two physicists) even led to the ideological conflict and rupture with China, where Mao continued to fight individualism. Although the film is no propaganda (= a gentlemanly goose), his production may well be a reaction to this alienation between comrade states. However, the enlightenment remained poor. The democratic centralism (= the expression of deviating morals is forbidden - seriously!) continued to be the state policy during the whole existence of the Soviet Union. This spiritual climate, in combination with a strong work ethics, may indeed foster the self-destruction of people in the would-be interest of the common good. Unfortunately I doubt that the uninformed watcher, who by nature adheres to individualism, will pick up this message from the film. I hope that you enjoyed my comments (if so, don't forget to check off "useful: yes"). By the way, IMDb actually pays you. While browsing through reviews I noticed one by a Rumanian, who shares my interests. And following his strand of reviews I stumbled over Nine hours of a year. What an amazing way to save time.

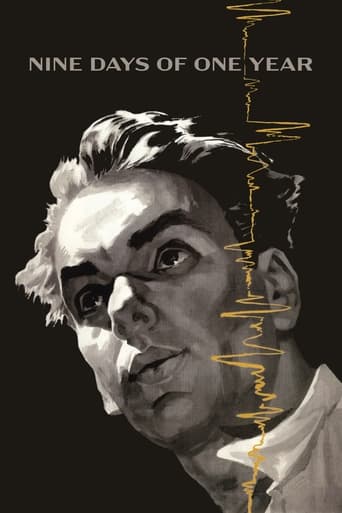

... View MoreNine Days of One Year refers not to nine consecutive days but rather to the Narrator of the film cherry-picking nine important days in the lives of two nuclear scientists and the woman they both love. The movie is set during the recent thaw in the time of the Cold War and uses the same lead actor we saw in The Cranes are Flying, the great Alexey Batalov. The director, Mikhail Romm, strives to reveal a community that had been veiled during Stalin's years. Ilya, Gusev, Lyolya; three physicists connected by bonds stronger than friendship, are tasked with illuminating the mysterious world of science and technology that had (and is) often closed to the public. An amazing achievement for its subject matter, the film was both produced and set in the time of the thaw; it is a film that claims in the very beginning through its Narrator that besides scientific inaccuracies committed here and there, all other facets of this movie are as close to representing the truth as possible. One can sense immediately that the film does not merely seek satisfaction in developing and propagating a story, whatever merits contained within notwithstanding (be it setting, theme, special mechanics, character development, dialogue, screenplay); it has incorporated a narrator to expedite the process while maintaining a basic necessary structure. The film instead yields many questions about the nature of scientific discovery and the potentially deadly consequences contained within those discoveries that affect both the scientific community and mankind at large. In fact, so great is the feeling of impartiality in the presentation of these questions, an agenda so strong that the characters cease to be themselves and turn into the mouthpiece of a tangible abstraction, an unnamed character both invisible yet omnipresent. We first become aware of it when Sintsev's manic obsession with his work in the nurse's room gives way, suddenly, to a moment of complete clarity and sensitivity to Gusev, the man who had been exposed to 200 roentgens of nuclear radiation; Sintsev suggests that Gusev find a girl before it is too late. How very uncharacteristic of a man who was just earlier celebrating his scientific breakthrough and ready to keep working even though in Gusev's words "he had killed himself" due to the exposure. Other times amid the scientific banter, theories, thought experiments and the like littering the movie, comes more transcendent ideas, detailing the correlation of scientific progress with the advent of war, a conversation played out by two scientists, whose conclusion is that the interests of science are aligned with those of war. Ilya and Gusev may be two more vessels for this omnipresent guiding voice while Lyolya seems to be purposefully granted immunity; for she is granted her own private thoughts, and is the one character who doubts herself as a scientist and instead thinks first of herself as a wife. Ilya questions the ultimate implications of scientific discovery and asks, "What good does it do?" Gusev, however, the character most immersed in the scientific realm and obsessed by his work, perhaps offers the greatest and strangest consolidation of the essence of the film. In a letter closing out the film, written to Ilya and Lyolya, he draws a picture of the three holding hands and asks to grab a bite to eat at a local café. The scene is a breathtaking exposition that humanity is more important than progress, which of course can be read as a refutation of the communist ideal.

... View Morefirst virtue - Russian flavor, result of precise recipes. than - brilliant performance , nothing new when the cast is represented by Batalov and Smoktunovsky. but, more important, the script. it is a Soviet story but root is not science, not a love story, not the sacrifice of a remarkable man for humanity benefit but the existence like huge puzzle. images, music, the light, the force of shadows, all are ingredients of an universal tale and about reasons of small and ordinaries gestures. and it is not a surprise because a great director and a magnificent cast are wise parts for a form of poem in images, not exactly an art film but a film of ideas, behind propaganda command, before Perestroika wave.so, must see it !

... View More