I like the storyline of this show,it attract me so much

... View MoreIn truth, there is barely enough story here to make a film.

... View MoreA film of deceptively outspoken contemporary relevance, this is cinema at its most alert, alarming and alive.

... View MoreExactly the movie you think it is, but not the movie you want it to be.

... View MoreI was 11 when this film was based. I used to watch the news and hear about the conditions within the prison and when the prisoners went in hunger strike. Didn't know about the "blanket" and "no bath" policy. So I watched this film with a very small understanding. There is very little dialogue in the film. The pictures tell the story. A prison officer going to work. A new prisoner saying he wanted to wear his own clothes. Being made to strip in front of a group of prison officers. The first sight of the cell which was so visceral I actually thought I could smell how bad it must have been. We are introduced to Sands (played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender) when he is taken to be washed and have his hair cut. I knew there was violence on both sides, however seeing that scene shocked me. Badly. I didn't know if I could watch the rest of the film. However, I'm glad I did. When the prisoners are given gaudy clothes and are in normal cells, they decide to make a point and start wrecking their cells. What follows had me in tears. In the Roman times, the army used to used decimation as a way of punishment. The punishment was death by clubbing or stoning. The scene with the prisoners having to make their way down a corridor with riot guards on both sides, hitting their shields to scare and using their batons to hurt, was reminiscent of this. Sands and his priest Dom meet and Dom tries to talk him out of the hunger strike accusing Sands of wanting to commit suicide and become a martyr. I've read that the two actors stayed with each other and practiced that scene over 10 times a day. There is no camera movement until near the end. It is one seamless shot. And it was done in 4 takes. There was also a scene where an officer was cleaning up the nightly urine which the prisoners emptied under their doors onto the corridor. Again, one camera until towards the end and it was beautiful. Never thought I'd call watching someone clean up urine beautiful.The last part of the film shows Sands at the end of his hunger strike. Again, not much dialogue; we just watched Sands get more ill and thinner to the point where he cannot stand the weight of clothes on his skin.It's diffic to say I enjoyed it as it's not a fluffy, feel good movie however it was a powerful film and I'm glad I did watch it.

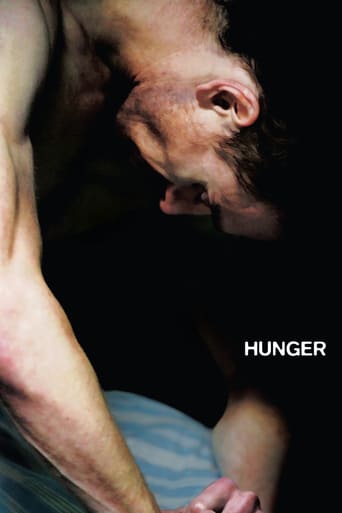

... View MoreHunger shows us Irish Republican Army (IRA) activists, whom prisoners demand to be treated as political prisoners (their goal was to separate Northern Ireland from the UK and re-emigrate to Ireland), receiving inhuman treatment, being humiliated and having to cope with daily violence, led by Bobby Sands (Fassbender), decide to go on a hunger strike to have their orders met. Not deepening in the political aspect of the story, Steve does show the dehumanization suffered by both prisoners and prison guards, beautifully done, with incredible takes, marvelous dialogues, it's a heavy film that is not easy to digest, but it's worth it to be seen. Besides, Fassbender still delivers a performance like Christian Bale in The Machinist (2004), leaving you totally paralyzed.

... View MoreConsider how Steve McQueen captures a character's morning in his debut feature film Hunger. He uses extreme close-ups to gradually unveil the strict routine of getting ready to go to work. The man is silent and efficient; he tucks a napkin into the folds of his shirt like a scientist slipping into his lab coat, and observes the food as more or less one of the many requirements of the experiment. We see him silently check under his car for a bomb, and nervously glance along the empty street. A POV spies on him from behind a curtain - it's his wife, who we realise must also undergo the same agony each morning, gripping her hands tightly together as he turns the key in the ignition. He is Maze prisoner officer Raymond Lohan, who sits alone in the cafeteria and does not indulge in locker room talk. What we observe is the learned, robotic discipline of a man who cannot afford to make mistakes or become emotionally invested in his work. McQueen offers another close-up of Lohan against a mirror, a face straining in pain. And only after have we become invested into his life and curious of his struggles does the film reveal bloody knuckles, and the revelation that another person somewhere else is in much more pain than he is. By the time McQueen returns to the same sink half an hour in, our feelings and sympathies have been changed because of what we have witnessed. For years before hitting the big screen McQueen made short films, many of which were looped as exhibits in various art galleries and museums. These roots are evident in Hunger, which eschews classical narrative and storytelling and instead opts to wade into the vague and often ill-defined territory of art film, preferring enduring images over explanations. Much of the first half of the film is filled with moments that could define it: the camera swooping over the sh*t-stained walls and finally descending onto the dishevelled figure of Bobby Sands, the slow, silent burn of a hallway leaking puddles of the protester's urine, the way the world slows down as a wall separates the beatings and a lone, sobbing prison guard, singled out for his youth and naivety. It's brutal, senseless violence, as evidenced by the wall of sound and pain that the prisoners are marshalled through, or the way water droplets hit the face of the lens as they are forcibly bathed. But as much as McQueen strives for realism with his hand-held and guttural sound design, he can't help but aestheticise until it's not merely tragedy, but grandiose tragedy. Sands has had plenty of time, and turned his own faeces into a swirling piece of art. A hole in the cell window grating allows a shaft of white light to peek through, and a prisoner marvels at a fly that crawls upon his fingertips, not merely an insect but a symbolic representation of the freedom he craves. The treatment of the final days of the martyr Sands outdoes all these. The most discussed segment of the film are the two unbroken shots of the conversation between Fassbender and Cunningham, and for good reason. Like the better cinematic priests (think Brendan Gleeson in Cavalry, or any of the religious figures in Doubt), Cunningham is inserted not as a moraliser but as his own character, able to understand the complexity of the situation and offer his own perspective. Before they descend into rhetoric they engage in small talk, as Moran teases (he doesn't object to the sacrilege of the bible for a smoke either), and McQueen is able to make us understand that this is a routine they have endured before, and that through the seventeen minutes they always come to the same impasse. Moran sympathises and does not simply condone; although Catholic doctrine states that suicide is a sin, he is more interested in Sands' end goals and well-being. Forget the eternal suffering of your soul, what about your physical body and mind now? The pair are so well-versed in the exchange that they are on the verge of cutting each other off and jumping to the next line, or at least Cunningham's Moran is, sensing that his time is running out to save this man's life. Although much has been said about the symbolic meaning behind Sands' story, the visible result is that it paints him as a man of utmost conviction, able to shoulder the burden and responsibility of darker deeds for the greater good of others. But a story simply isn't enough. There is a lot more context here, and the film deliberately avoids engaging with the historical and political baggage of the situation, diminishing it to personal struggle. It depicts the increasingly fragile state of Sands' body, dissolving untouched meal trays onto each other, shoving the camera up close and asking us to cringe and avoid averting our eyes. McQueen doesn't filter Sands' last stand through the lens of a wider protest, or evoke the desperation of a group of men resorting to their remaining weapon, but reduces it to body horror, and renders the iconic visage of Sands into a withered metaphor for determination and conviction. Fassbender may be good at this, but he lacks the symbolic connection to the thirty thousand Irish residents who voted him into the Fermanagh and South Tyrone parliamentary seat during the hunger strike, so he's merely a physical body in decay. Not that this deters McQueen, however. In his close he all but denounces the stylistic precedent already established, and resorts to burying Sands in myth, superimposing flights of birds over his body, and bathing him in angelic light to transform his plight into rapturous martyrdom. No doubt Cool Hand Luke and Michelangelo's Pietà were consulted. And finally McQueen stumbles clumsily into formalism, revealing a younger Sands surveying the piety of the almost deceased older Sands, yet it almost seems to be a look of pity.

... View MoreAmazing film. Michael Fassbender and Liam Cunningham is one of the best scenes I seen lately. Steve McQueen is something like no other. In my personal opinion, I was studying the trouble in Northern Ireland when I watch it and I believe it having that little bit of information and understand on how bad thing were during the time help me really get the full experience of the film. I had seen Shame and 12 Years a Slave so I already knew how amazing Steve McQueen is, but after watching these film I was able to enjoy his amazing directions which were highlighted in Hunger. Knowing that this was on of Fassbender's first major films is outstanding, you can really see his talent in his film. Again amazing film!

... View More