Wonderful character development!

... View MoreThis is How Movies Should Be Made

... View MoreGood start, but then it gets ruined

... View MoreThis movie feels like it was made purely to piss off people who want good shows

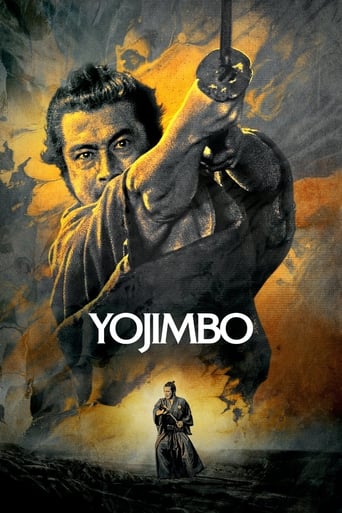

... View MoreFirst of the Yojimbo/Sanjuro set, Many of the shots which would be used in a Fistful of Dollars the start of Dollars trilogy. The Samurai walking in the town with the dog with severed hand in his mouth puts tone of the whole film in that one scene. This film has many more and overall you should this influential action masterpiece.

... View MoreIn 1860, during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate,a rōnin (masterless samurai) wanders through a desolate Japanese countryside. While stopping at a farmhouse, he overhears an elderly couple lamenting that their only son has given up farm labouring in order to run off and join the rogues who have descended on a nearby town that has become divided by a gang war. The stranger heads to the town where he meets the owner of a small Izakaya who advises him to leave. He tells the rōnin that the two warring clans are led by Ushitora and Seibei. The silk merchant and mayor back Seibei while the sake brewer is allied with Ushitora. But after sizing up the situation, the stranger says he intends to stay as the town would be better off with both sides dead.

... View MoreThe opening credits are overlaid on the back of a samurai's head, and his feet, ragged sandals and all. Close-ups that give little indication of where he is going, until a dog turns up with a human hand and a father and son quarrel on giving up a boring life for high stakes gambling and fighting. He observes, even as he is momentarily pushed out of frame - he adjusts his shoulders, scratches his head, and continues on in his worn out clothes, clearly signalling that the time of the samurai is coming to an end. The violin is foreboding and in mourning. Some versions will insert ugly English captions over this sequence, but Kurosawa is not one of those directors that needs this sort of aide. Slowly and surely, we begin to understand this rōnin, this master-less warrior, the lonely wanderer of the western. He continues this facade as he enters the town. As he first encounters Ushitora's band of mercenaries, he is surrounded and buffeted by both background and foreground, and the mass of bodies and that gigantic hammer dwarfs him. Later, as he effortlessly cuts down three of them and establishes his ability, they eye each other on equal grounding. He makes a quip towards the casket maker that rivals Harmonica's about horses. He then walks with the same walk as he opened with, but which now carries an air of dominance and dismissiveness that he rides for much of the film. And the two sides react appropriately; they slobber over him, shower him with gifts and offers in hope of his allegiance. Kurosawa makes the two sides distinct. The town is conveniently aligned much like the prototype western settlement, with a runway down the middle for those dramatic confrontations. To the side, innocents peep out from behind shutters and bars, too frightened and held hostage by the warring factions in their little village. There are some immaculately detailed shots that layer several perspectives in their deep focus; the worrying father, the conceding mother, Sanjuro musing. There is a genius segment in the inn, where Sanjuro observes the conflict from all perspectives. First he physically separates the two sides of the frame from the centre, as Inochicki goads the casket maker and he thinks on his approach. Then, he tracks and follows the band of thugs through the windows, and then finally unveils both sides and their various allegiances. Gonji, the inn owner, provides running commentary, but it is the power of Kurosawa's images and compositions that stand on their own. He cackles from high above on the bell tower, as the two sides inch towards each other and struggle to commit the opening blow. The other character who is unafraid of action and bloodshed is the snake-eyed Unosuke, in one of Tatsuya Nakadai's finest performances (perhaps second only to his gaunt King Lear in Ran). His eyes are bottomless pits of black that gleam with anticipation of violence, matching his devilish smile. He brandishes the deadliest weapon in the film, a little metal gun that signifies the coming age and the death of the sword, and unleashes it without hesitation. In the finale, Sanjuro seems to recognise this defeat even within his victory, and offers a surrender to a gun that may or may not be loaded. Opposing these pure moments of drama are the scenes that seem to make up the dark comedy aspect of Yojimbo. These meld less seamlessly than Kurosawa might have liked. There is the oafish, heavy-set Inochicki with the monobrow and not an ounce of brains who hurries from fight to fight. The constable Hansuke giggles and scurries like a scared little rat, if only to further the illusion of a town in chaos and disorder. And in one peculiar moment, a weak Sanjuro makes his escape in a casket, but then insists on being let down in order watch the Seibei house be burnt down because it "sounds interesting".But what comes after that is so magnificent. A hanging corpse in the foreground forces the eyes to the stumbling, beaten figure that stands in the midst of billowing smoke and ash (so powerful that Leone would later mirror this same exact shot, among others). One man versus a gang, slowly shuffling towards each other as the cymbals and hi-hat provide an eerie rhythmic tension that would not be out of place in a Morricone score. There is no longer the sense of swagger and otherworldly strength that Sanjuro and the samurai of the old possessed, even as he dispatches the group...but there is a message for the fleeing trembling boy, that seems to echo a sentiment from the beginning of the film. The age of heroics is over, the gun is here...and those who cannot bear to take part in the coming massacres best run home to mommy.

... View MoreYou've just sat down to watch a film by Akira Kurosawa. Make sure you're not squeamish by the sight of decapitated limbs and swords smashing into samurais. Kurosawa is the original master of the violent Japanese samurai flick. I wouldn't be surprised if Quentin Tarantino gets down on his knees and prays to him by his bedside at night. This genre of film that he created is based upon the period of "Jidaigeki", which has its origins in Kabuki theater. It's the music of the swords. It's the story of brave samurais fighting in honor of their families and towns. It might sound foreign to you, but it's really not. "Jidaigeki" genre movies supplied many concepts and ideas that inspired what we all know as the Spaghetti Western. Well, you should know, it was a little too inspired, but that's a story to get into another day. Kurosawa's films have an amazing shelf life to cinephiles across the globe, and none more important than "Rashoman". But I have just watched, what I feel to be the best example of Kurosawa's influence on the western genre, and what I feel to be an especially compelling and entertaining piece of work, "Yujimbo". "Yojimbo" has a story, not that complicated, and told so many times, you'd think you've sat down to watch some clichéd schlock. As I've stated before, it's about the lone hero, or in this case, the lone samurai, who somewhere along his travels comes upon a village that has been split between two rival gangs. In the town are the struggling families and business owners that are victimized day in and day out by the constant robberies and assaults from the gangs, as well the insufferable and corrupt police officer that gleefully capitulates to the two rival gangs. They ravage throughout the town, and out of sympathy for the townspeople, or perhaps just for the hell of it, the lone samurai decides to pit the two against each other in order for them to fight to death. It is out of his virtue to save the town from the hands of crime, and he's well aware of it very early on in the film, as he notices a dog carrying a severed human hand around the town. This is the Wild West, or shall we say, the wild east. In this little town, the lone samurai helps cause chaos and showdowns abound as the rival gangs fight for territory. It's almost comedic how much manipulation he has over them. I loved how it didn't always work out. For instance, the lone samurai is seen overhearing a conversation of the hotel owners planning to kill him in order to not pay for his stay. It seems like he's been causing a lot of trouble, much to the chagrin of the town's people. I really enjoyed the balance between action, story and humor. Unlike "Rashoman" that captivates with a rigid, dramatic story with a lot of unsightly, gruesome characters trying to eat each other alive, this is a fun little western. It's a classic in the genre as it gets. The lone samurai even bears a strange resemblance his American counterpart, Clint Eastwood, complete with his squinty eyes and scowl. The man in question is Toshiro Mifune, and he has a spectacular track record with Akira Kurosawa. Every time he collaborates with him, you're going to get an unbelievable performance. In "Rashoman" he was the insane, giggling bandit, and here, he's the silent, master of the sword, who could cut your arm off with a single blow. He's the original badass movie star. Even when he goes down, he goes down hard. When the lone samurai gets captured towards the end of the film, he is seen slowly and painfully making his mistake. This probably was my favorite scene, for it demonstrates Mifune's range as an actor, and his willingness to discomfort himself for the benefit of the story. The picture also has a really unique soundtrack. I overheard someone in the audience chuckling about it, for it sounded a little similar to "Big Band". The music fits the attitude of the picture splendidly. It's a big, loud soundtrack to a big story. The cinematography was also very ambitious for it's time, and Kurosawa's main cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, noticeably builds upon his great talent of the image since Rashoman. The battle sequences are sweeping and detailed with all the blood and guts intact. The spectacular scene in which the lone samurai is escaping is staged and shot beautifully. Miyagawa holds an exceptional gift of bringing the Edo Japanese era vibrantly to life. "Yojimbo" is a violent epic, and one of Kurosawa's most startlingly good achievements. It's entertaining, thrilling and a credit to the history of Japanese cinema.

... View More