Boring

... View MoreA Disappointing Continuation

... View MoreJust intense enough to provide a much-needed diversion, just lightweight enough to make you forget about it soon after it’s over. It’s not exactly “good,” per se, but it does what it sets out to do in terms of putting us on edge, which makes it … successful?

... View MoreIt's a good bad... and worth a popcorn matinée. While it's easy to lament what could have been...

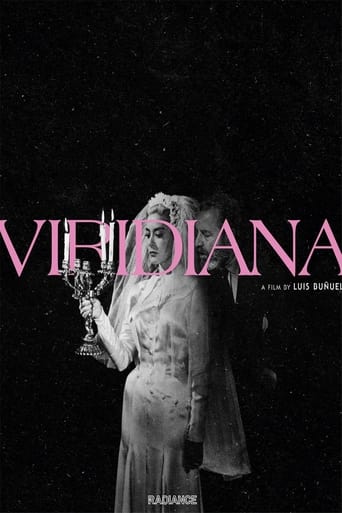

... View Morethe clash between different worlds. and the try to have a common language. a critic against Church. and the special beauty of Silvia Pinal. love. and obsessions. fear and the need to self definition. nothing new at the first sigh from Bunuel. but Viridiana is a return to the origins. so Spanish than it becomes universal. bitter and harsh tender. a masterpiece because it is more the film of nuances than the result of a story. a delicate embroidery of lost beauty and about the shadows as cage of idealism. and for that Viridiana remains seductive - for the grace to present an ugly universe in each of its levels. and to propose a sort of cold view about the ordinary choices of innocence.

... View MoreLuis Buñuel is one of those directors I really want to love. Los Olvidados was a winner for me but Exterminating Angel, Discreet Charm, Belle de Jour and now Viridiana are films I consider good but not great. Perhaps their meanings just fly over my head. There's no doubt that Viridiana has Buñuel's finest cinematography. With its deep whites and blacks and brilliant framing, it's one of the finest shot films of the 60s at the very least. But there's something about the story that doesn't sit with me right. I just don't know what Buñuel is trying to say with his stories. The plot progresses and it's interesting watching this character be tested throughout these obstacles and it never feels like it's trying to say something that isn't cryptic. Is it about morality? Class comparison? Religion? I don't mind when films don't spell it out for me but when a film like Viridiana is so exquisitely shot and acted, it's quite unsatisfying and a little frustrating to not get anything out of it. Maybe it does touch those who love it in a way that I just don't relate to at all to even recognize. Still, very good on the surface.7/10

... View MoreSorry Buñuel fans, I know comparisons are odious but if I had to pick the definitive Maestro between him and Fellini, I'd say Fellini without a doubt. And Viridiana gives me the best arguments. Let's face it: this is a dated movie, hardly a classic. The raw value of a classic is above all its resilience to time and V. doesn't do well through that test; even more considering that its lasting value comes from that "slap in the face to Franco" and from a rather gratuitous blasphemy scene. Also, the movie is not the fruit of an unique stroke of creative genius, but instead a work with sources of inspiration in two traditional Hispano American cultural creatures.Most Buñuel reviewers fail to recognize where he gets his real sources and influences. For ex. they say of Phantasm that it got no structure, when the fact it has one, that of a "novela picaresca", a genre born in Spain in 1554. The protagonist of the N.P. is usually a man born in the lowest strata of society--gen. an orphan--who grew up having to endure numerous hardships under the yoke of cruel, miserable masters, including assorted clerics and blind men. Structurally a NP is a sequence of short, unrelated, stories, their only common link being the "picaro", its protagonist. About Phantasm, Buñuel himself said once that his initial idea was to use one single character as the link, so I'll rest my case there. You can do further research, but let's just say the mood of a NP is usually ugly, one of utter disenchantment, even if the picaro tries to keep a brave face when telling his story--because he's also the narrator—spicing it up with dark humor. (For ex. in Lazarillo de Tormes the essential NP, the way he got rid of his blind master--he says--was to put the man in front of a post, telling him there was an irrigation ditch in the way, so he had to jump as far as he could—-so you can see there the traditional inspiration for the ugliness and cruelty of the beggars here). The other traditional source which inspires the first part of the movie, is Hispano American melodrama, mostly Mexican and Spanish.Contrary to North American melodrama, which focuses on intrigue, plot twists, clash of personalities, Iberoamerican melodrama is corny, sappy and it focuses mainly in getting the waterworks going. One plot line that was used and abused for decades was for ex. that of the poor woman who gives birth to and illegitimate child, who is then taken away and given in adoption to a rich family. Decades later the still poor woman goes to work as a maid in a wealthy household and guess what...You got it, the master of the house is her lost son. So when the last episode comes out, their coming together, there's no one single handkerchief to be found in the whole city.The main character here comes right out of Hispanic melodrama; that's why I don't like it, specially when Pinal overdoes the virginal vestal. It is as if once given her marching orders she would have switched herself to make for the sappiest soap opera heroine. Come on, I've known girls like that but never one like her. In real life they usually lose that innocence as soon as they step out of the convent. Viridiana is unrealistic, a caricature; no wonder the movie seems to become real only once the beggars are left alone. It would have been better if Buñuel had thought of her as just another down to earth character, but it seems he was bent on keeping her above the crowd as some kind of a metaphor. Of a Spain torn between its traditional forces maybe--the Church and a decaying land aristocracy--but I fail to see there in what Arrabal's Jorge can be compared to Franco. Franco wasn't a urban liberal at all but an ultra conservative, uber traditionalist, dictator and war criminal. That's also why, returning to Viridiana, I prefer actresses from outside doing Hispanic heroines when it comes to melodrama. Hispanic actresses can be good at comedy, satire--as Pinal certainly is in Simon and Exterminating Angel-but when it comes to melodrama they seem genetically programmed to ham it up, to tune themselves to get the audience's waterworks going full blast, or else they may think they have failed.So, while Fellini was instrumental in giving birth to a new film genre, Italian neo-realism and then went to create his own universe--Fellinesque we call it--where the characters born of his own fruitful imagination, memories, could evolve at ease, there's no such equivalent in Buñuel's work. Buñuel got propelled into surrealism in his association with Dali, of course, but he is more apt at showing his philosophy of life—his disenchantment with mankind and its pathetic attempts to reach the transcendental, its habit of debasing everything it touches; his own amazement at the weirdness of the situations we find ourselves many times in life--and also at bringing memories and dreams to the screen, he was more apt at that than at creating a new universe where his own characters could live and evolve--as Kafka did in literature and Fellini in movies. That's why many Fellinis are timeless, I could watch them many times over, while quite a few Buñuels are already irremediably dated, as Viridiana. I say 6.5/10, of interest mostly for film students and Buñuel fans.

... View MoreRegardless of the inhibitions that it may engender, it's always a matter of great cachet and honor to review the work of a virtuoso like Luis Buñuel. Calling Buñuel merely a movie-maker would not only be an understatement but also an invidious remark. Buñuel was a pioneer in every sense of the word and his works avant garde and highly influential. He is regarded as the father of surrealism in cinema and his predilection for the morbid and the obscure had earned him the tag of a 'fetishist'. Buñuel's directorial debut, Un Chien Andalou, a prototypical work on Surrealism, is a living example of Buñuel's vision and imaginative genius as a movie-maker and more importantly as a student of cinema. Buñuel was averse to explaining or promoting his work and ironically his surrealist works are so personal, distinctive and elaborative in style and manner that no one but Buñuel was worthy of judging or explaining them. Fortunately for me the first Buñuel movie that I have ventured to review does not deal with surrealism. Viridinia is a story of a young nun whose inexorable resolve for redemption ironically takes her to the brink of moral corruption. Viridinia revolves around bourgeois (middle class) modus vivendi and deals with controversial themes of gluttony, blasphemy and adultery which have been an integral part of Buñuelesque oeuvre. Buñuel was a staunch maverick and fittingly his iconoclastic works relentlessly flouted the bourgeois morals and the very root cause of bourgeoisie plight - the conservatism and hypocrisy camouflaged in the preaching of Catholicism and Christianity. Viridiana not only stands equal to the task of mocking organized religion and hypocrisies associated with it but just like other Buñuel works also manages to bring in a humanistic element with a somber yet sensual touch. The questions that Buñuel manages to pose through Viridiana are so straight and naked that even a saint of divine proportions, or a champion of human rights will not only look askance in want of candor but will also be forced to squeal in ghastly terror while trying to answer them. Such was the impact of Viridiana on the The Roman Catholic Church that the Vatican's official newspaper published an article calling Viridiana an insult to Catholicism and Christianity. The movie was banned in Spain and all its prints were destroyed as per the orders of the Spanish autocrat, Francisco Franco. These exaggerated responses were clearly not responsive of the subject material that Viridiana showcased but were the mere consequences of the questions it posed and the answers that it demanded.Viridiana is a young nun on the verge of taking her final vows. She is asked by her Mother Superior to pay a visit to her estranged uncle, Don Jaime, who has repeatedly expressed his keenness to meet Viridiana. She remembers that her uncle was never there for her whenever she had needed his support. Despite the absence of an emotional urge, she decides to pay him a visit simply out of courtesy. Don Jamie is a recluse rotting in the abject solitude of widowhood, which is making him more vulnerable and desperate with each passing day. Upon meeting his nubile niece, he notices a striking resemblance to his deceased wife. This ray of hope reinvigorates a new sense of purpose in his life as he decides to put forth a marriage proposal in front of Viridiana. He implores her to wear his wife's wedding dress which she reluctantly obliges. When his maid, Ramona informs Viridiana of his intent to marry her, she is appalled, and Don Jaime appears to have dropped the idea. However, Ramona secretly drugs Viridiana drink and Don Jamie carries the unconscious Viridiana to her room with the intention of raping her, but falls short of doing the ignominious. The next morning, he bluffs that he has made her his, and hence she is no longer pure enough to return to the convent. Seeing her undeterred, he concedes the truth, but fails in convincing her fully. Viridiana immediately leaves for the convent but at the bus stop the authorities reveal her that Don Jamie has committed suicide and has left his entire property to her and his illegitimate son, Jorge. Deeply disturbed, Viridiana decides not to return to the convent. Instead, as an act of penance, she brings home an assemblage of beggars and devotes herself to the moral education and feeding of this underprivileged lot. The things become a bit more complicated on the arrival of Jorge who shows a strong inclination for Viridiana. What ensues is a series of amazingly bizarre yet poetic sequences which can best be cherished through viewing rather than description. The penultimate scene depicts the beggars posing for a photo sans camera around the table in which they seem to collectively resemble the figures in Da Vinci's Last Supper; a chair substitutes for the door which now cuts into the fresco, and removes Christ's feet. This scene, in particular, earned the film the Vatican's opprobrium. The controversial finale adds a completely different dimension to Viridiana elevating it to new levels of cognitive interpretation. In a nutshell, Viridiana is a truly fascinating cinematic experience catapulted to new heights of magnificence by Buñuel's mastery and his unflinching ability to depict the sad and abysmal reality of living under the influence of false and misconstrued religious tenets. Viridiana along with The Diary of a Chamber Maid (1964) are great means of acquainting oneself with Buñuel's oeuvre and can serve as an excellent mock exercise to prepare oneself before exploring Buñuel's exceedingly challenging surrealistic works. 10/10http://www.apotpourriofvestiges.com/

... View More