An action-packed slog

... View MoreIf the ambition is to provide two hours of instantly forgettable, popcorn-munching escapism, it succeeds.

... View MoreClever and entertaining enough to recommend even to members of the 1%

... View MoreThe movie really just wants to entertain people.

... View MoreSince we are now in Cold War II, this movie deserves to be revisited. Ten minutes into the film with no dialog, and then twenty, and the music just keeps your stomach turning to the very end with no spoken word. I'll give it a star and a half just for this bold silent experimentation in the talkies era. This film predates European art films that would emerge a decade later and emulates the great Russian experimental films of the silent era with its splendid photography and acting. I'd give Ray Milland another Oscar for this. By the end of the movie he does look ten years older.

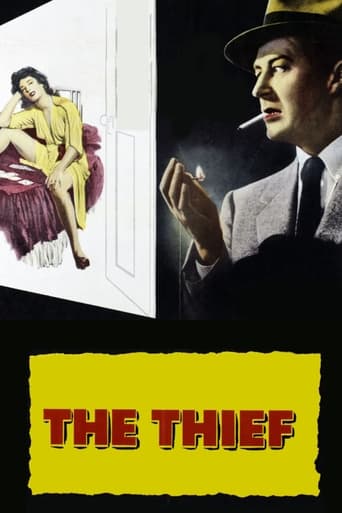

... View MoreThe Thief stands as the first American Film since Charlie Chaplin's City Lights without any spoken dialogue.Directed by Russell Rouse this 1952 noir is a propaganda film without any of the leaden anti-Communist dialogue that other films of this type contain. In fact the film has no dialogue! It's funny how first impressions stay with you. When I first saw The Thief it was at a Film Noir series at the Film Forum Theater in New York.The Thief stands out for its special way of objectifying the isolation of the central character with film elements such as mood-inducing lighting, scripting, and especially music.The lack of dialogue and Ray Milland's marvelous performance visually communicating the angst and secretive nature of the lead character is something to see to appreciate.What stands out in this film is the lack of dialogue. At the outset this motivates us to watch more closely than if we were given dialogue to help drive the action along.With its blast of a raining phone in the very first frame of the film as the camera moves over to show us the anxious Allen Fields lying fully dressed on his bed waiting, we understand that sound and sight over spoken language is what will be the currency of this film.Hats off to Ray Milland and the wonderful score because just as in the early films of the silent period all the plot points of the film are understood trough purely visual means, pushing the film to the level of pure cinema.The musical score for the film that Herschel Burke Gilbert composed says volumes about the character Allen Fields, and his emotional state.Gilbert received an Academy Award nomination for his music score for the film and one watching will tell you why. Gilbert creates swells and moods to support the facial expressions and other physical language that Milland utilizes to show us what is happening with Fields and his eroding state of mind.The dialogue-less film is definitely a stylistic approach to this subject matter. It is very unusual but primarily because we are used to a dialogue-driven plotted film style.The technique does begin to seem forced into the second half of the film especially in exterior scenes where one would normally hear people talking as ambient sound.The scenes with the FBI would have some sort of dialogue, especially in those where agents are being prepped on who to investigate.Once the viewer gets with the approach that the filmmaker is taking though, the lack of dialogue can be understood as part of the overall theme of he voice-less nature of the Spy character in films.Some things are left unexplained though and this could have been added to create more depth in the story line. We never learn why Fields is stealing secrets for the enemy. Is he being paid? Is there a wife being held captive? These pieces of the puzzle may help. Without them the story feels poetic without substance.Ray Milland gets extra credit for creating such a memorable performance. His Allen Fields seems cut from the same cloth as his character from The Lost Weekend, angst-driven without solution.No one can drink whiskey or smoke a cigarette quite like Ray Milland, with his sense of exclusive attitude while simultaneously embroiled in some deep emotional turbulence.For anyone interested in Film Noir styling taken to exceptionally expressive levels this film will show you things you may not have seen before.The night exteriors are textbook noir examples of lighting and camera. In this case the ambient sounds of the Washington D. C. locations are contrasted well with those of the New York City locations, especially the wide shot of Milland's Allen Fields arriving in the beautiful Pennsylvania Train Station before it was demolished.Although the interiors are stage sets there is attention paid to creating surroundings that support the 'silence' of spy Allen Fields especially the cage-like apartment where Fields waits for his final phone call.

... View MoreDon't' be put off by the 'gimmick' of a dialog-free movie. THE THIEF is an engrossing, extremely well-made movie. Right off the bat we can expect quality with Ray Milland in the lead: the man could act. And THE THIEF is a graphic demonstration of how acting requires much, much more than good line-reading. Milland immerses himself in the drama from the word go, and we almost never think of him as an actor until the end, when the impact of the film really hits. This is a powerful performance, in the league of some of the best from the silent era (only more realistic in style). Russell Rouse presents us with a story that bristles with suspense in some scenes. First time around, it may be a slight challenge to know what's going on, but it's soon clear that exact details are not important. We only need to know that Milland plays a Washington D.C. scientist who is microfilming top-secret government documents and passing them on to agents who remain obscure. His main contact is played very nicely by Martin Gabel, an actor with a face perfect for sinister, wordless intrigue.Just as important as the acting and directing is the music score. Hershel Burke Gilbert must have outdone himself for this project. This is an excellent score. Never obtrusive, always supportive of the action; pleasing, but never calling attention to itself. The music really makes the film work. An example of how intelligent the approach to the scoring is comes at the film's climax when Milland is followed to the very top of the Empire State Building, the music stops completely for about ten minutes. The effect is downright Hitchcockian -- an extremely effective sequence.Also worthy of mention is the persistent use of locations: D.C and New York in 1952 are almost characters unto themselves. This is another superb film that document the bygone look of some great urban locations. Very highly recommended.

... View More'The Thief' is a gimmick film, and the gimmick is more interesting than the film itself. Without the gimmick, this movie is a fairly banal Cold War drama. The central character is an American nuclear physicist (played by Ray Milland) who, at regular intervals, gives classified information to spies for a foreign power. (The enemy nation is never identified, but surely it's either the Soviet Union or a Soviet satellite nation acting as intermediary for the Kremlin.) Eventually the physicist's guilt and his latent patriotism overcome his other motivations, and he turns himself in.The gimmick is that this feature-length film tells its story without any dialogue. I've seen at least one reference book which lists 'The Thief' as a silent film. That's incorrect; 'The Thief' has a soundtrack, with conventional ambient sound throughout the film, and occasional human noises such as grunts and screams ... but no coherent dialogue.The gimmick is an interesting one, but it becomes wearying. On at least three occasions in this movie, Milland's character is home alone when his contact man rings him up. We see Milland staring in horror at the 'phone as it rings. And it rings. And it rings some more. Once we realise that there's never going to be any dialogue in this movie, we also realise that Milland isn't going to pick up the 'phone. It's not quite clear what's happening here. Is Milland allowing the 'phone to ring, unanswered, because the number of rings constitutes some sort of signal between Milland and his contact man? Or is Milland supposed to answer the 'phone, but he's too gutless to pick it up? Anyway, each time the ring-ring routine commences, it always ends the same way: eventually the scene fades out (with the 'phone still ringing), and then we fade in to Milland on his way to the next rendezvous. At several other points in the film, the narrative gets bent out of shape to enable the action to proceed without dialogue, in a situation where plausibility makes dialogue essential. (By the way, I *really* dislike any movie in which a 'phone keeps ringing or a baby keeps crying, and we're forced to listen to this because nobody on screen responds to the situation.)'The Thief' benefits from some extremely realistic locations, notably in one sequence in which Milland drops off his microfilm by sticking it in a drawer of a card catalogue in a reference library. Dozens of people are present, and none of them notice what he's doing. (Also, the hushed atmosphere of the library makes the movie's no-dialogue gimmick - in this particular scene, at least - very plausible.) The contact man in this scene is played by Martin Gabel, an American actor who affected a crisp mid-Atlantic accent; it's interesting to see Gabel here in a role that doesn't rely on his distinctive speaking voice. There's also a suspenseful sequence in which Milland must climb an outdoor stairway to deal with a 'tail' who's been surveilling him.On the negative side of the ledger, we get that old atom-bomb cliché which has afflicted other movies better than this one, including 'Torn Curtain' and 'Pickup on South Street': namely, that a mathematical formula is somehow so powerful that spies will want to steal it. That's nonsense, that is. The atomic-bomb secrets which were bandied about by Rudolf Abel and Julius Rosenberg were specific engineering schematics of military ordnance. In 'The Thief', Milland is just peddling algebraic equations ... and we're expected to believe that these fiddly bits of maths can somehow change the balance of power.The basic implausibility of this film's premise, strained even farther by the no-talking gimmick, is made a lot more bearable by the documentary-style cinema-verite techniques used throughout. Not one shot in this film looks like a studio set-up. At one point, one of Milland's contacts (who has just picked up the latest microfilm) steps into a crossing and blunders into the path of an uncoming vehicle. A woman pedestrian sees this, and she reacts. Because of the no-dialogue gimmick, which makes this seem like a silent film with dubbed-in sound effects, I expected her to react silently. Impressively, she screams; the movie would have lost all remaining plausibility had she not done so.Ray Milland (a seriously underrated actor, despite his Oscar) gives a strong performance in a role which allows him only a very limited emotional range and no dialogue at all. 'The Thief' would have been much more plausible if it had skipped the no-dialogue gimmick and told this movie conventionally. But without the gimmick, this would be a much less interesting film: the gimmick is much more compelling than anything else that's on offer here. I'll rate 'The Thief' 6 points out of 10.

... View More