Lack of good storyline.

... View Moren my opinion it was a great movie with some interesting elements, even though having some plot holes and the ending probably was just too messy and crammed together, but still fun to watch and not your casual movie that is similar to all other ones.

... View Morea film so unique, intoxicating and bizarre that it not only demands another viewing, but is also forgivable as a satirical comedy where the jokes eventually take the back seat.

... View MoreThe best films of this genre always show a path and provide a takeaway for being a better person.

... View MoreFilm theory professors are inclined to force their students to find and reflect on nonsensical connections, such as mulling about the relationship between a recent Italian film and the most historically important Italian genre. This was my try to integrate La Grande Belezza in the frame of Italian neorealism.Firstly, a clear definition of 'genre' is needed to approach Italian neorealism from this perspective. Structural film theorists created the term 'genre' in order to detect underlying patterns in a group of otherwise unrelated film texts in opposition to the prior focus on the oeuvre of a distinguished director (Altman, 2006). Given their origin, it is logical to assume 'genres' are contained -and thereby defined, wholly within the film text. Altman refutes this seemingly independent nature, stating that critics and spectators themselves generate and modify mental expectations for each genre (2006). Accordingly, the context, in other words the social and political situation surrounding the film text, is at least partly responsible for the generally accepted meaning of a particular genre. In the continuum from text-dependent to context-dependent genres, a specific genre is situated near the extreme of the context side, namely Italian neorealism.To elaborate, the Italian neorealism was a reaction to the propagandistic use of film during the fascist regime of Berlusconi from 1922 to 1945 (Wagstaff, 2007). The Italian film directors of the immediate post-world war II strove, similar to many counter-movements, to a complete opposition of the prior film production. The realistic aspect of their films is therefore not solely based on an aesthetic reason, but also on political and social motivations. Ben-Ghiat has even stated that the Italian neorealist cinema was part of the transition period of Italy towards a democratic structure, film was more suited than any other medium at the time to express the need to reintegrate the humanist ideals of the Enlightenment into the national image and culture (2008). Contrastingly, Altman has noted in his article of 2006 that some historians have linked the realistic nature of the neorealist movement to a forced aesthetic due to the absence of production materials and general poverty. Bazin diverges from this purely practical view as he evaluates the neorealist films as a reminder that realism is in fact an aesthetic choice. He attributes the choice for this aesthetic with political reasons, relating the Italian neorealist movement to the revolutionary cinema of Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Dovzhenko (1967). Although on an aesthetical level the neorealist cinema is more similar to the social realist cinema under Stalin.In comparison, Paolo Sorrentino's main aim in La Grande Bellezza (2013) could be deemed to be similar in its intention, i.e. presenting the social and political reality of a specific place and time. Additionally, In terms of space it has overlaps with Roberto Rossellini's Roma, città aperta (1945) and Vittorio De Sica's Ladri di biciclette (1948). However, even though La Grande Bellezza contains many connections with Italian neorealism on a textual level, no film critic or spectator would ever deem it to be a neorealist film. The context of post-world war II Italy is too strongly interwoven with the label of 'Italian neorealism'. It is therefore impossible to make another neorealist film, no matter how closely it follows the aesthetics and content. In light of the previous conclusion it seems to be more productive to view Italian neorealism not as a genre such as it was defined at the beginning of this essay, but as a film movement that liberated the Italian film production from its propagandistic abuse by the fascist regime. Italian neorealist films had to strive for simplicity in order to achieve this goal of purification, thereby being forced to limit their possibility of content and aesthetics (Bondanella, 1993). However, since the context has changed filmmakers are now no longer bound to these strict rules when they want to convey a realistic portrayal of the contemporary social and political situation. Plus, Hsu writes in his article of 2006 about the recent trend of incorporating many different genres in a single film text and the overall blurring of the distinct dividing lines between genres. These circumstances suggest the unlikely nature of any filmmaker restricting himself to the narrow regulations of the genre of Italian neorealism. La Grande Bellezza, which displays influences of the films of Rossellini and De Sica yet incorporates a greater variety than just those sources, is more common.Specifically, Sorrentino's film contains surrealistic scenes, adopts stylistic schemata from the CinemaScope aesthetic of the early American widescreen, plays with colour contrasts to add symbolical elements to the scenes, references the visual style of other media such as music videos, and contrasts wildly varying tones and atmospheres throughout its runtime. In conclusion, regarding the style of filmmaking La Grande Bellezza is as far removed from the simplistic archetype of a neorealist film as possible. A more apt comparison is the bombastic and multiperspective Roma (1972) by Fellini. The consensus in genre theory dictates that genres change over time as they are reassessed and redefined by all involved agents. A genre that is not able to change due to its dependency on the context, as is the case with Italian neorealism, is therefore destined to die out. In the specific case of Italian neorealist cinema many film critics and theorists point to De Sica's Umberto D. (1952) as the end point of the movement. However, Paolo Sorrentino and many other international filmmakers have proven that even though Italian neorealism has ended as a genre, it is still influencing contemporary film production and this will likely continue in the future. The fundamental motivation of the neorealist filmmakers was to liberate cinema, a goal in which they succeeded. Other directors have opted to celebrate that freedom, instead of clinging to the movement that provided their freedom. La Grande Bellezza is a good example of a film made in this liberated style thanks to the collection of influences that Paolo Sorrentino integrated within his work.Altman, R. (2006). Film, genre: London, British Film Institute 2006.Ben-Ghiat, R. (2008). Un cinéma d'après- guerre : le néoréalisme italien et la transition démocratique. (Cinema after the War: Italian Neorealism and the Transition from Fascism to Democracy). Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 63e année(6), 1248.Bondanella, P. (1993). Viaggio in Italia The Films of Roberto Rossellini: Camebridge University Press.Wagstaff, C. (2007). Italian neorealist cinema : an aesthetic approach. Toronto ; Buffalo, N.Y.: University of Toronto Press.

... View Moreto Felini. to the Rome who remains an obscure legend. to a kind of Visconti universe. to a refuge. eccentric, bizarre, comfortable. a great trip in a well known universe. full of cultural references, in a sort of escapes from yourself in the most profound yourself. a magnificent show. or another La bella vita. the same, after decades. but so different for the courage to be itself. a homage and a return. to the old things remaining, always, fundamental.for the extraordinary beauty, for memorable scenes, for a sort of confession of another Giuseppe di Lampedusa, for the scene of meeting with Fanny Ardant, for the venerable nun , for the dose of fascinating freedom.

... View Morethe film is sometimes boring, sometimes beautiful, sometimes even unpleasant. I would remark the beauty of Rome in the night walks, the city always ahead of its people. What I don't like is the actor playing the leading role, he is not at all elegant, or handsome or interesting by any means. The Marcello Mastroianni from la dolce vita is here a good actor ( everybody says )but without any charm or any looks to be part of the high class society

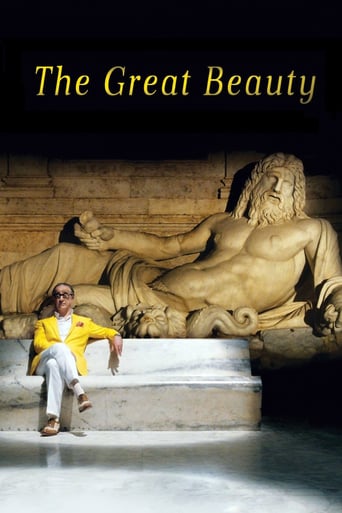

... View MoreThis is one of the most visually remarkable films I've ever seen. It captures the spirit and beauty of Rome. The camera delves into corners and crevices of the night life and the daytime of this eternal city. This is the story of a man who has debauched his way through life. At sixty-five, he begins to wonder what happened. He is highly respected for his single book (he never wrote another) and has casual friends who are more users than true companions. He hearkens back to a relationship he had earlier, where a woman he could have had, instead ends up with a close friend, who, it turns out, never made her happy. The actions of the characters are vacuous and relatively feckless. He encounters artists who are mostly show and little substance. We see self-indulgent women wasting their lives. This is certainly more about the journey than the result. The people who are most solid in this man's life are the one's he takes for granted. Death seems to be around the corner and what do we do until that happens? Does it make any difference what we do? The beauty here is all around, but is wasted on most of these people.

... View More