Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

... View MoreThis is one of the few movies I've ever seen where the whole audience broke into spontaneous, loud applause a third of the way in.

... View MoreThis is a small, humorous movie in some ways, but it has a huge heart. What a nice experience.

... View MoreThere is definitely an excellent idea hidden in the background of the film. Unfortunately, it's difficult to find it.

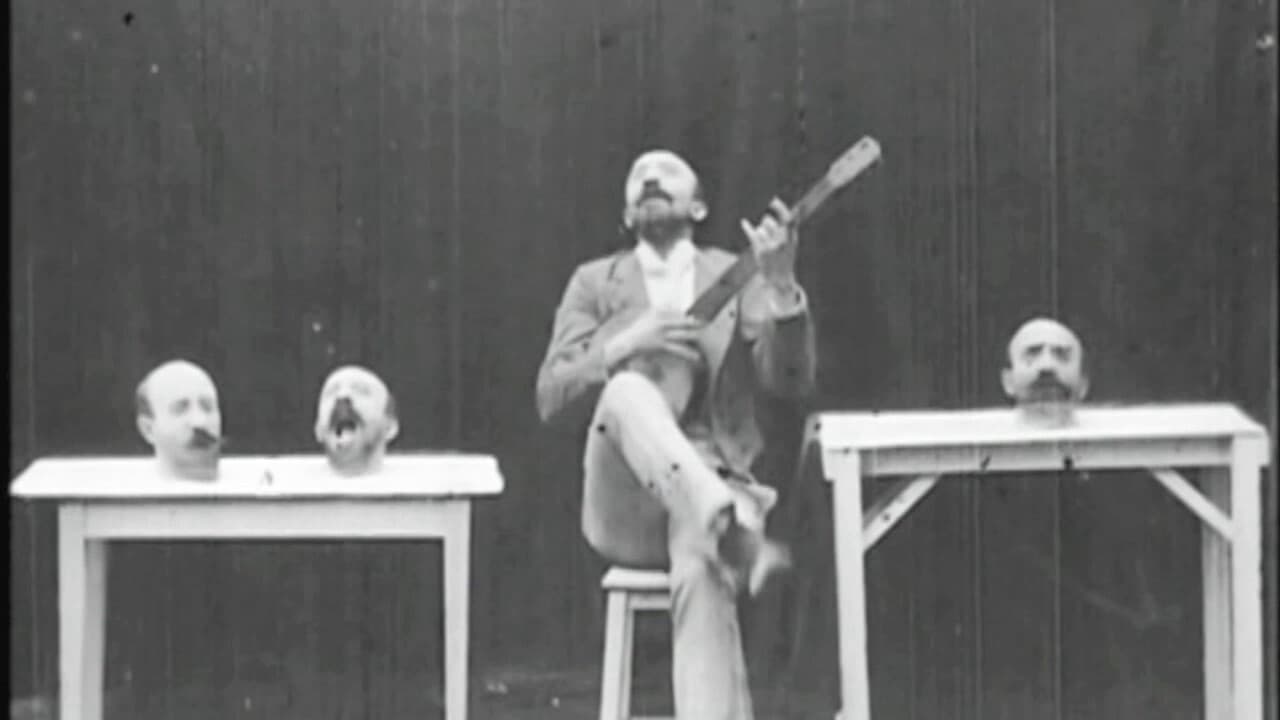

... View MoreIt's hard to believe that this brief effort from 1898 still exists and is viewable for just about anyone thanks to the delights of the Internet. It's another early effort from Georges Melies that utilises simple stop motion camera tricks to quite wonderful effect. Here, the emphasis is on ghoulish head-play, as a man pulls off his own head which then multiples until a number of heads are singing and laughing on the tables about him. Seen today, the special effects seem primitive and obvious, but imagining how this must have looked back in 1898. I can well imagine that people were fleeing in fear. Melies was a true genius.

... View MoreIt's tempting to see the two great French pioneer film makers, the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès, as two opposing poles of the cinema — the documentary depiction of reality set against the drive to enhance reality, and show things that previously couldn't be shown. But this is over-simplistic. First it underestimates the extent to which, even in their earliest films, the Lumières were taking aesthetic decisions about exactly which slices of reality to depict, and how — consider the camera placement and timing, for example, in L'arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat. Not long afterwards, they took to re-enacting events they weren't able to film for real.Meanwhile Méliès, for all that he seemed to take a more forward looking and adventurous approach to the possibilities of cinema, was deeply rooted in a much older tradition. He was a stage magician and illusionist, owner of Paris's Théâtre Robert-Houdin, an heir to the staged spectacle, the Fantasmagorie and the magic lantern show. Attending the Lumières' first Paris exhibition in 1895, he immediately saw the potential of this technology in achieving illusions he'd already been pursuing by other means. The brothers refused his offer to buy one of their machines, but within a year he bought a projector from Robert Paul in London and built a camera himself.Méliès' tradition is explicit in this film, which is staged as if in a theatre, with the man himself as the magician performing to an imaginary audience, and even taking a bow at the end. But the illusion presented would be impossible to achieve so convincingly without film. Méliès several times removes his own head and places it on a table, then regrows a new one, until he's surrounded by three detached heads, all jabbering away animatedly at each other to prove how alive they are. He attempts to wrangle them into singing together, but soon gives up in frustration and extinguishes two of them with a blow from his banjo.It's funny and visually striking but also poignant — the film externalises our experience of conflicting inner dialogues. How much we've sometimes wished to shut up some of our own jabbering heads with the swat of a banjo.A wiry, balding man with a naturally comical appearance, Méliès regularly performed in his own films, often decomposing and distorting the image of his own body, and particularly his head. He's always worth watching and this is a particularly fine example of his eccentric, athletic and manically energetic style — you can believe he's capable of bullying reality into new shapes by force of gesticulation. Like many of the pioneers, he never reaped the just rewards of his foresight, and it's rather saddening to see his energy here and then remember that he ended his career scraping a living selling sweets and toys from a kiosk at Gare Montparnasse.

... View More"The Four Troublesome Heads" is one of the earliest surviving films by Georges Méliès to employ the multiple exposure technique, or superimposition effect. He used the technique earlier in "The Cabinet of Mephistopheles" (Le Cebinet de Méphistophélès)(1897), but it appears to be lost. (There's also a brief superimposition in "The Magician" (Le magicien)(1898), for a head on a stand.) It's uncertain whether Méliès or George Albert Smith introduced the trick to cinema, although what seems to be the earliest relevant film that I know of is the aforementioned film by Méliès. Smith tried to patent "the invention of double exposure applied to animated photography", but that was frivolous since the technique was already in use in still photography. Somewhere from around July to October 1898, Smith made at least six films that employed the trick. In "The Corsican Brothers", "Photographing a Ghost" and "The Mesmerist, or Body and Soul", Smith used multiple exposures to make transparent ghosts. He also used the technique, coupled with a masked camera lens, to create a scene-within-a-scene vision in "The Corscican Brothers", "Cinderella", "Faust and Mephistopheles" and "Santa Claus". In regards to masking the camera, Smith, indeed, seems to have introduced it to motion pictures. Méliès would later use masking for his multiple-exposure trick films, such as "A Mysterious Portrait" (Le Portrait Mystérieux) (1899) and "The One-Man Band" (L' Homme orchestre) (1900). Nevertheless, the uncertainty is somewhat moot given that Méliès and Smith are known to have had discussions around the time of these inventions, and both filmmakers were leaders in exploring the possibilities of motion pictures.The superimpositions of "The Four Troublesome Heads" are not for ghosts, but, rather, are for four cloned heads of same texture; this effect of same texture is achieved with the black background. In this film, Méliès accomplished the headless and no body effects by masking himself with black clothing. Additionally, a dummy head was used while the Méliès with a body moved the heads to the table. For these transitions, Méliès employed his second essential trick of stop-substitutions (a.k.a. substitution splicing). The camera operator stopped the camera – the scene was rearranged – and filming resumed. They are essentially jump cuts touched up by post-production splicing. Méliès had already used the stop-substitution trick in such films as "The Vanishing Lady" (Escamotage d'une dame au théâtre Robert Houdin) (1896), and it would continue to be probably his most used trick during his film-making career.Yet, these tricks are only of a technical and filmic history interest without Méliès's unique showmanship and enthusiasm, which was largely responsible for the immense popularity of his films in his own day and the preference of today's audiences for the films of Méliès over those by other early filmmakers. Méliès was, indeed, more cultured and absorbed with theatrical traditions than were his contemporaries. Later, filmmakers would surpass much of his theatrical style, but at the time of this film, he was leading the way with it.

... View MoreI must agree with Méliès' granddaughter's description of this film. While there isn't really a plot, the film exudes pure genius in its construction. Although it looks like a single 55-second scene, the film actually combines dozens of snippets of performances and does so amazingly fluidly. The effects in this film could easily be done today using computer graphics, but would have been difficult to achieve before the 1990's. And yet Méliès was able to pull them off almost a century before that.Although Méliès would later go on to produce some dramatic films, the most famous being his "Trip to the Moon", the pacing and energy of his later works generally fall far short of what he exhibits here. Further, while many of his later films have at least some noticeable mismatch edits or other problems, his technique on this film is perfect. Absolutely amazing.

... View More