Not even bad in a good way

... View MoreDreadfully Boring

... View MoreBoring, over-political, tech fuzed mess

... View MoreThe plot isn't so bad, but the pace of storytelling is too slow which makes people bored. Certain moments are so obvious and unnecessary for the main plot. I would've fast-forwarded those moments if it was an online streaming. The ending looks like implying a sequel, not sure if this movie will get one

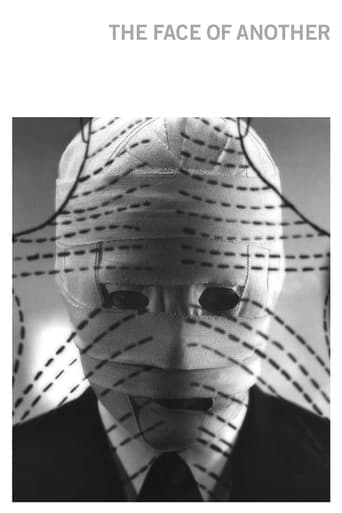

... View MoreJames Quandt's strident narration of the "video essay" that accompanies the Criterion release of THE FACE OF ANOTHER complains about the reception the film received in the United States on its initial release. He quotes the critics of the time: "extravagantly chic," "arch," "abstruse," "hermetic," "slavishly symbolic," and "more grotesque than emotionally compelling." Stop right there! These critics knew what they were talking about.The film combines several hoary and not particularly profound narrative contrivances. Here's a man attempting to seduce his wife, pretending to be another person--this was old when THE GUARDSMAN first went on stage and has been done countless times. Then there's the classic mad scientist, presented with very little nuance, delving into Things that Man Was Not Meant to Know. Related to this is that the story is only able to exist by grossly underestimating man's ability to adapt to the unknown. (An example is the 1952 science fiction story "Mother" by Alfred Coppel in which astronauts all return insane when confronted with the vastness of space.) These primitive tropes are shamelessly built on a simple narrative situation that is completely unable to carry them: a man with a disfigured face getting facial reconstruction. This happens all the time, so what's to "not meant to know"? If all this isn't enough, Teshigahara tacks on an unrelated, completely separate set of characters in their own undeveloped narrative that even Quandt thinks doesn't work. The dialogue by author/screenwriter Kobo Abe is risible, sounding like something out of a grade-B forties horror film.To disguise the paucity of the film's narrative, Teshigahara has tricked it up with what Quandt admiringly calls "its arsenal of visual innovation: freeze-frames, defamiliarizing close-ups, wild zooms, wash-away wipes, X-rayed imagery, stuttered editing, surrealist tropes, swish pans, jump cuts, rear projection, montaged stills, edge framing, and canted, fragmented, and otherwise stylized compositions." These arty-farty gimmicks (and more) are, of course, hardly "innovations." They were endemic in the early sixties. Their extensive use seems a vain attempt to disguise the film's shallow content. Quandt also sees great significance in the many repetitions in the film: I see only repetition.But even that is not the film's worst problem. Teshigahara often seems like a still photographer lost in a form that requires narrative structure. His inability to develop a sustained narrative makes the film seem far longer than its already-long two hours plus. Things happen, but the film doesn't really progress. The end result is little more than a compendium of tricks and narrative scraps borrowed from others.

... View MoreThis is amazing cinema all the way through, in story, in sound editing, in cinematography, in acting, in lighting, and editing. The story is all about a lonesome disfigured man, and feels like it could have been written by Tennessee Williams or Ernest Hemingway. The direction was trippy and haunting in the way that Roger Corman movies are. It's like a precursor to "Abre los ojos"/"Vanilla Sky", but with a pace all its own, a more thoughtful, careful pace, that builds subtly. But just like those movies, this one also has no clear resolution. After all that arduous torture, we are left without any shining piece of truth, without any humor, but beyond that, we are not left even with any lasting issues to discuss or contemplate. We are only left with a sick, hopelessness. That's why I say, it's technically and dramatically alluring, but without payoff. I'm glad I watched it once though.Goes well with "Memento".

... View MoreA brutal commentary on self-image and the way that appearances can change the attitude and ideals of a person that is one of the best films I've ever seen. The way that Okuyama changes throughout the film is incredible. He starts off as a brutally wounded man, who is afraid to go out in public due to his horrible disfigurement. He realizes how important looks are and all he wants is a new face so that he can blend back into society and be with his wife again. There's no desire to be attractive or important, he just wants to be normal. But once he gets his new face, his attractive appearance turns him into a completely different man. He buys flashy clothes and walks around with an attitude of superiority and importance in a world where he is really just a stranger. The film does a remarkable job of showing just how important appearance truly is, even if you think you can look beyond it. This is shown through Okuyama's wife, who pretends like she loves him even though he is horribly disfigured, but she ends up refusing his sexual advances due to it. Teshigahara uses bleak tones and minimalist sets as a way to show the isolation that society creates do to it's one-dimensional view of forming opinions on people merely due to appearance. These settings also do a great job of focusing the viewer on the characters instead of flashy visuals and elaborate sets.I thought that the Psychiatrist was also a very complex character as he becomes more and more interested in his experiment with Okuyama's new face and less interested in Okuyama himself. He becomes greedy and selfish in his desire to mass produce the masks, but Okuyama's greed compels him to reject the Psychiatrist's wishes and look out merely for himself. This greed makes him a very dangerous man who is hanging on the edge of a breakdown through most of the film, until an encounter with his wife finally sets him off. It's the Psychiatrist's greed, though, that ends up being the true horror of the film. Okuyama realizes the dangerous monster that this mask has turned him into, and does the only thing he can think of to stop him from harming the world. It's the Psychiatrist's greed, though, that unleashes the beast of Okuyama into the world which leads to the abrupt and shattering finale. The paradox of a physical monster versus a psychological monster is absolutely sensational. In the beginning he is deformed on the outside, but as he becomes normal and beautiful on the outside, he ends up being a terrible monster internally. There is only one thing that I can really complain about, and that is the entire story of the "Facially scarred young woman". All of her scenes felt really out of place and added nothing to the fantastic commentary and intelligence of the plot. Everything with her was just unnecessary, but this was just a mere chink in the grand masterpiece that the film embodies as a whole.

... View MoreIn the search for self-discovery, one who suffers from an inferiority complex cannot mask who they really are from the public. This film brought certain questions to my mind: Which is worse? Suffering the physical and external conditions of a burned face, or, suffering the emotional and internal conditions of low self-worth? In the beginning, Mr. Okuyama is a self-loathing and debased man who in consequence of his own self-rejection polarizes the relationships he has with others. The laboratory incident that subsequently disfigures his face causes Okuyama to finally have reason to unleash the inner-poison he has festered inside for a long time. The inner-poison he carries is the self-absorbed and accumulated hatred he has for himself. He tries to blame his wife for not showing the affection he wants from her by stating that it is because of his external ugliness that she rejects him, when really this is a mere mask for his internal ugliness he has not yet accepted. Okuyama's arc will deal with his transformation from reproached and depraved thinker to confident and strong human participant.After receiving his new face from a complete stranger, he "allows the mask to take over" and become who he always wanted to becomea confident human participant. But it seems only a transient form of hiding from who he really is. Soon, his true and inner-self begins leaking through the mask; as seen when the retarded hotel daughter realizes who he is, and, when his attempts to seduce his wife fail. The attempts fail because she claims she already knew it was him despite his cover-up. When he realizes that the mask is wearing off, he tries to resort to alcohol to cover up his insecurities. Despite his efforts to cover-up who he really is, the truth of his character haunts him like a shadow that doesn't depart.The most pervasive ideology that I observed within the Japanese culture was the idea of isolation. During the beginning credit sequence, seas of people are shown mindlessly crowded together and slowly walking along the city streets of Japan. With so many blank faces to observe and not a clear direction on who to focus on, the viewer becomes anxious and feels rather isolatednot connected to any of the people shown. It brought to mind how seemingly insignificant all of us sometimes feel when walking in a crowd of people, asking ourselves: "Who am I to be anything important when others are more capable, beautiful, and intelligent as I?" As the film demonstrates, it is a personal subject matter on the nature of identity. The Japanese seem to feel that the search for one's identity is one that is lonely, fearful, and full of angst and despair. All of these ideas are exposed through Mr. Okuyamaa man who has not accepted who he is and attempts to mask his true identity from situation to situation.Further evidence of this isolation is seen in a very literal rendering of the idea of losing identity. Seas of people are seen once again walking along the city street towards Okuyama and his psychiatrist, this time, however, with no faces at all. The psychiatrist says, "The pathway to freedom is a lonely journey." To me this spoke of how when one becomes enlightened to the truth of the world (that is, the way it really is), the lonelier it becomes because of the fact that most people don't question their identity. They just seem to be mindlessly drifting from situation to situation, never once taking thought or examining the nature of their existence. The loneliness also increases because the enlightened doesn't have anyone to share his/her experience with that will understand let alone accept their position. It reminded me of Plato's cave. Okuyama is attempting to break free of the chains that bind him inside the dark and damp lit cave (i.e. the world and his place in it) and see the truth and beauty of the outside world. The journey to do so is a difficult onefull of doubt, discouragement, feelings of low self-worth, and confusion.The idea of internal and external beauty is also an important idea inside this culture. The seemingly insignificant side-story of the beautiful woman with the scarred face helped demonstrate this idea. When she is seen walking along the city street and flirtatious chants are thrown her way, she turns her face in their direction and immediately the chants cease. They become aware of her external uglinesstheir once playful manners have now turned into cold and harsh rejections. The Japanese culture (like most) seems to be suggesting that the world has not yet learned to accept inner beauty, but is still judging the books by their covers. The same judgment is intertwined into Okuyama's character. He is constantly thinking that others are judging him and that they will reject the "monster" that he supposedly is. When he receives a new face entirely, he still believes that others, namely his wife, are rejecting him. It goes to prove one thing: No matter how attractive the masks we wear appear outwardly, if the soul is scarred, we will still be ugly on the outside.

... View More