Nice effects though.

... View MoreExcellent, a Must See

... View MoreThis is a dark and sometimes deeply uncomfortable drama

... View MoreAll of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

... View MoreThe war theme was quite popular during the post-war period in different kinds of arts, especially film production. Therefore, we can observe lots of films, which were under strict censorship of governments, about the particular battles, persons or big events with a purpose to agitate a patriotism and undermine the reputation of the ex-enemy. Therefore, on the background of these films, Kon Ichikawa tried to shoot a film about the war, without single propaganda for or against anyone. Instead, he "filled" the film with the abstract thoughts about life, which are tightly connected with Buddhism, during the war and, literally, lots of songs and hymns. That is why you could get it as Japanese musical about war with some deep meaning. Due to the shooting date, I cannot properly assess the picture and sound quality: the main thing - you see and hear something. However, there is no doubt about the cast. The play of every soldier of Captain Inouye's group was felt as a representation of real soldiers of WWII because you could see individual thoughts and feelings towards particular events around them. Moreover, Rentaro Mukini, who had a starring role, showed the exemplary model of commander, who cares about the people's lives more than heroic actions with the clear death of the whole troop. Still, Mr. Yasui, who played the central personage of the whole film - Mizushima, made a great effort to persuade the audience that there could be a sudden enlightenment and decision to stay at Burma, despite that you have a chance to go back home. Sudden decision to become a monk. Certainly, the director was inspired by Zen Buddhism, especially the Rinzai school and its idea of gradual enlightenment. According to broad claim, this film was as recognized Buddhistic, due to the several signs as the speech of the monk "Burma is Buddha's country". But, I could not agree with it. The presence of temples and monks adds certain level spirituality and, in this case, serves as vital bond in the screenplay for more dramatic upshot rather than a sacred message to the audience. To sum up, the audience of this film is certainly sufficiently narrow. If you want to be in this group, you must have: 1) certain interest in the World War II history; 2) desire to watch the 2-hour-long black-and-white grainy film; 3) patience toward simple and obvious plot. At the end of watching, you can surely say that you watched worthy Buddhistic film from respected Japanese director.

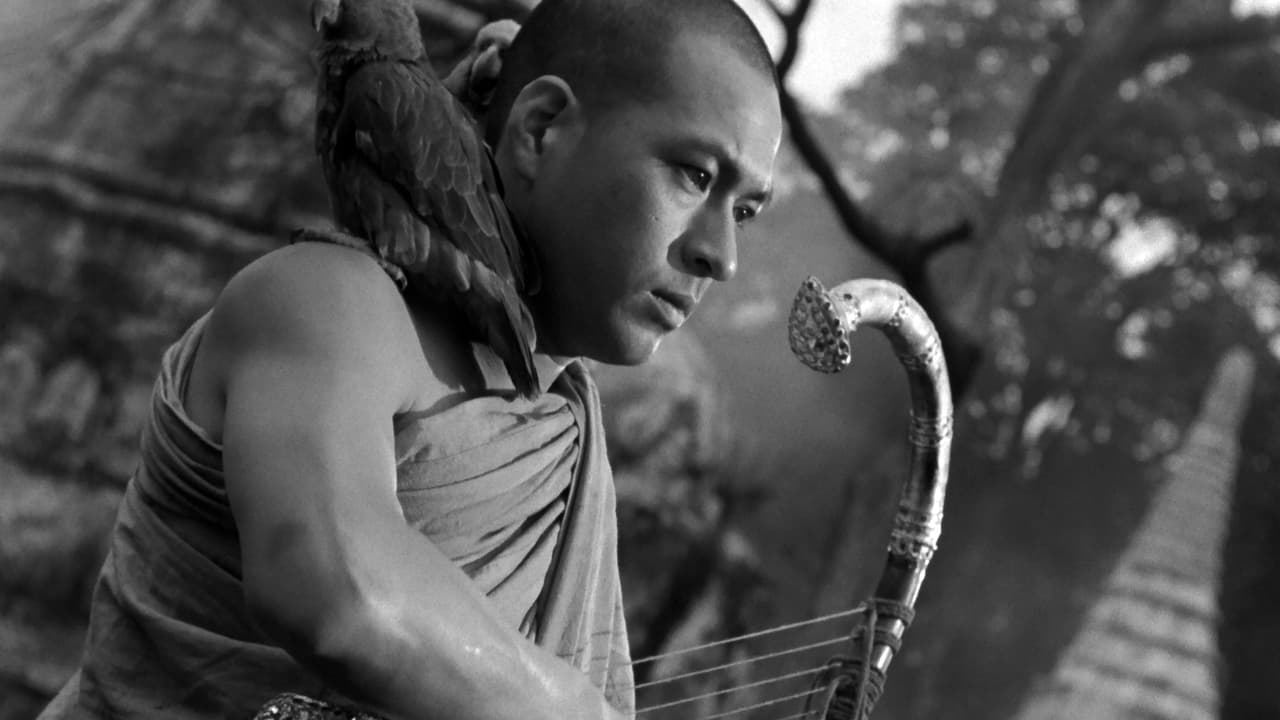

... View MoreTowards the end of WWII, a group of Japanese soldiers struggle through the chaos of national disintegration, trying to reach the border through the Burmese jungle. Their Captain is musically trained and forms them into an ad hoc male choir in order to maintain morale. Foot soldier Mizushima plays the titular instrument and as such become a talismanic figure in the group. When he later disappears and suffers an existential crisis, his fate comes to obsess the group as a whole.Ichikawa's iconic piece contains a strong anti-war theme that survives beyond its 1945 setting. Mizushima's troop are timeless, soldiers dreaming of homes, wives, town festivals; clinging to nostalgia to guide them home and fighting on for each other rather than any greater cause inspired by the imagined national community. Much more identifiable with the period are the troop holding out against the British even after national surrender, fanatics looking to die for an Emperor who has forsaken them rather than return to their families and rebuilding of the community. Among these men, there are no songs.Mizushima's conversion from soldier-musician to selfless monk symbolises a state of reflection that follows all armed conflict. The film has been criticised for failing to confront the barbarism of the Imperial army, but this lack of identification with specific national failings is what gives the film a theme that transgresses to other cultures, conflicts and evils - the coming to terms with a life to be lived in the aftermath of horror. The flaws on the Yamato spirit may not be interrogated, but the atrocities of war are present, most visibly in Mizushima's encounter with the rotting flesh of fallen comrades being picked over by scavenger birds. The framing is impeccable, and those looking for a quintessential Japanese aesthetic will be surprised by the extensive use of closeups. The music is spare and suitably evocative of military camaraderie and frightened young men coping far from home. Mizushima's journey is both symbolic and highly plausible, as is the reaction of his brothers-in-arms. Great cinema in its own right, and at the very top of the tree in anti-war movies.

... View MoreWhile a bit sentimental, it never veers into mawkishness, and the full five or so minute reading is one of the great humanist documents in cinema, perhaps even greater than Charlie Chaplin's speech at the end of The Great Dictator. Mizushima claims his new mission in life is monkdom, and helping to bury the war dead, and promote peace in the world. The film then makes an interesting decision, and one virtually uncommented on in any of the criticism of it I've read. After the letter is read, the film's narration (which opens the film, and is rather sparse) begins again. All along, viewers have been led to believe- via closeups of the captain's face during other narrations, that it is he who has been telling this film's story from some indefinite time in the future. But, no; the speaker, as the camera move sin, turns out to be a wholly anonymous member of the unit; one who had no prior scenes nor close-ups.Imagine, as example, had Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick, not opened with Call me Ishmael, and the reader only found out who the narrator was on the last page, and had to guess if the narrator was omniscient, or a member of the Pequod, only to be startled their guess was wrong. The reason this is so important, looking back at the film, is that a) the point of view change from the expected narrator to another recapitulates the confusion that the troop has over whether or not the monk they see is their comrade- thus letting the viewer 'feel' the confusion that the internal characters are feeling- albeit for a different reason, b) it makes the viewer question whether or not what has been shown is true or not, since we now know the narrator is not the reliable and honorable captain- a character we would trust as reliable. This ties the whole film back to the more fairy tale like quality of the source novel. The final reason, c), it forces the viewer to wonder whether or not he or she has assumed other things that were not so in the narrative, even if one accepts that all the anonymous private has revealed is true.This is an astonishingly effective device that Ichikawa employs, and coming on the heels of the straightforward and moving missive revelation by Mizushima, the audacity of Ichikawa's narrative sleight of hand erases any doubts over whether this film is great or not. It is as great a film as his later Fires On The Plain, which, narratively and tonally, is almost the complete opposite of this film. But, the fact that such a key element in the film has never been commented upon before shows how little most critics actually pay attention to the subjects they criticize, as well as how little they understand how even a small moment, or the slight use of a technique, can radically change the whole tenor of a work of art. This is too often because the critics approach art with their own biases in tow, rather than viewing the work on its own merits. Another moment that has gone critically unnoticed is the scene on the bridge, between Mizushima (dressed as a monk) and his troop. This occurs two times. The first time, the viewer is as confused as the soldiers are, but the second time, the narrator tells the audience it was definitely Mizushima. Thus, we know that Mizushima's ruse will be found out, and this diverts the narrative tension from will the soldiers learn the truth of Mizushima? to how will they learn it, and will they learn why? This is not an insignificant narrative change of direction, but one, again, which never seems to have stirred critics.The DVD, put out by The Criterion Collection, is well transferred- the black and white hues are brilliant. However, the DVD lacks an audio commentary- an increasing annoyance with Criterion releases ever since they went to their new C logo. There are too all too brief interviews with Ichikawa and Renataro Mikuni, who played the captain. There is a trailer, and only subtitles, again in white- another bête noir of Criterion, for white subtitles often are lost against the whites of a black and white film. Colored subtitles are a must if no English dubbed soundtrack is to be added. The insert contains an essay on the film by film critic Tony Rayns, but it's a rather pedestrian take on the subject. Akira Ifukube's score is solid; the only real highlights are the delightful harp playing by Mizushima.Overall, The Burmese Harp is a great film. It is not one of those razzle-dazzle works of art that is flashy, but it gets the job done, and invites rewatchings to elicit subtleties one viewing may miss. It also kills the old notion that all war films- even those with explicitly anti-war themes- end up celebrating war because of the battle scenes and those scenes which show individual valor. Both this film and Fires On The Plain kill that notion; the former by eliding almost all scenes of battle, and the latter by the sheer devastation of the results of war it shows. It certainly deserved its nomination for an Academy Award as best Foreign Film, as well as numerous other festival awards. Ichikawa's reputation is that of a serviceable studio director, and that may be true; but the two films of his I've seen are the equals of the best films made by the titanic Japanese triumvirate of Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, and Kenji Mizoguchi. Here's hoping he has a few more deviations from that norm others claim for him.

... View MoreAt the end of WWII, a Japanese platoon is stationed in the jungles of Burma, who have impressive singing skills inspired by their star musician, Private Mizushima...and his harp. Mizushima becomes separated from his company and is presumed dead. Stealing the robes from a Buddhist monk who saves his life, he disguises himself to avoid suspicion as he goes in search of the British prison camp where his platoon awaits repatriation, but is unprepared for the new perspective the stolen robes provide. The initial selfish act of theft contain the seeds of the thief's selfless future. Mizushima's spiritual transformation from a fake monk, thief and soldier of war to that of a genuine bodhisattva warrior (a peaceful 'warrior' of wisdom, compassion and generosity) is reflected in a wonderful and unforgettable scene where his platoon assembles for choral practice in front of a large reclining Buddha statue. As the platoon begins to sing, they are baffled by the mysterious and beautiful harp accompaniment that seems to emanate from inside the body of the Buddha statue, where unknown to the platoon, Mizushima, who is thought to be dead, has taken refuge... and has himself become an instrument of peace.

... View More