Very Cool!!!

... View MoreGreat visuals, story delivers no surprises

... View MoreThe joyful confection is coated in a sparkly gloss, bright enough to gleam from the darkest, most cynical corners.

... View MoreThis movie tries so hard to be funny, yet it falls flat every time. Just another example of recycled ideas repackaged with women in an attempt to appeal to a certain audience.

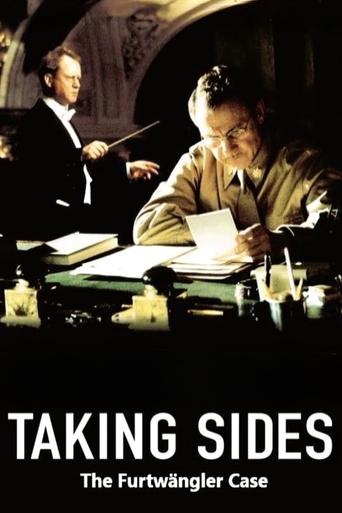

... View MoreBombs can be heard in the distance as Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is being performed in a church in Berlin near the end of World War II. The conductor, Wilhelm Furtwangler, portrayed by Stellan Skarsgard, continues the performance despite the wailing of air raid sirens and a spotlight scanning the windows. It is only a power failure and a darkened hall that ends the concert. Back in his room, the conductor is warned by Hitler's architect, Albert Speer, that it might be better if he take a trip out of the country and "get some rest." This scene opens the film Taking Sides, a fictional account of the investigation by Allied officials at the end of the war to find and punish Nazi collaborators as part of its "De-Nazification" program. No musician could work professionally until they had been cleared by the Allies and Dr. Furtwangler, who had remained in Germany during the war, was no exception. Directed by Istvan Szabo and based on a play by Ronald Harwood who also wrote the screenplay, the pre-trial investigation focuses on the role of the artist in a totalitarian society, specifically, whether it is more effective to leave the country in protest or remain to work against the oppressive government from within.The film relies heavily on three interrogation session conducted in an office above a museum between an overbearing investigator, U.S. Major Steve Arnold (Harvey Keitel), and a proud but humbled Furtwangler, perhaps the greatest conductor of his time and the last, great exponent of the German Romantic school. Under orders from his superior, a U.S. general (R. Lee Ermey), to "nail the bandleader" and hold all Germans responsible for their war crimes, Arnold keeps Furtwangler waiting outside his office, contemptuously calls him "Wilhelm" and talks to him as if he was personally responsible for the gassing of millions of Jews.Arnold's aides, Lt David Wills (Moritz Bleibtreu), a repatriated German Jew, and Emmi Straube (Birgit Minichmayr), the daughter of an officer who was executed for his involvement in the plot to kill Hitler, support the investigation but eventually express their distaste for Arnold's methods and try to bring a sense of compassion to the proceedings. Though the film engages in spurious speculations such as whether or not Furtwangler's secretary procured women for his pleasure before each concert and whether damaging evidence lurks in a "Hinkel archive," the real thorn of contention is that the conductor remained in Germany during the war while other famous conductors such as Otto Klemperer, Arturo Toscanini, Fritz Busch, Bruno Walter, and Erich Kleiber left. Some were Jews who had no choice. Others left out of conscience.As the prosecution shows newsreel clips of victims of the holocaust being thrown into mass graves, Furtwangler, a deeply conflicted man, becomes more and more on the defensive. When he is brutally questioned by Arnold about the high posts he accepted in the government, the concert he gave to celebrate Hitler's birthday, and the fact that his recording of the Adagio from the Bruckner Seventh was broadcast to the nation after Hitler's suicide, Furtwangler says that no one who was not in his shoes could appreciate "the tightrope he walked between exile and the gallows." He asserts that he was only a pawn in the power struggle between Goebbels and Goring, and that his continued presence in Germany was desperately needed to keep the spirit of resistance alive and nourish the soul of the German people in the midst of barbarism.In support of their conductor, musicians from the Berlin Philharmonic testify that Furtwangler was a man of high ideals who disdained politics, refused to join the Nazi Party, give the Nazi salute, or conduct concerts in Nazi-occupied countries, and helped countless Jewish musicians in need of money, employment, or an exit visa out of Germany. Though strong points are made on both sides, Szabo stacks the deck in one direction by portraying the major as a bullying and cynical Philistine in contrast to the intelligent and highly articulate artist (not the case in real life). By the time of the final session, Arnold has descended into little more than a self-righteous bully.The film ends with a postscript. It is Berlin, 1942, a different world than any of us know. The conductor is the real Wilhelm Furtwangler, a tall, gaunt looking man with only a patch of hair on his balding head standing astride the podium, a baton in his hand. In the audience are Nazis Heinrich Himmler, the chief of the SS, and Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister. Conducting a performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, a work of titanic spiritual struggle, Furtwangler does everything to guide the orchestra towards the realization of Beethoven's humanity. The musicians, however, as if possessed, unleash every ounce of the work's inner fury with reckless abandon.A long scream echoes through the hall, Alle Menschen werden Bruder, Wo dein sanfter Flugel weilt! (All the people will be brothers, dwelling under your gentle wing). In this setting, the words could not be more steeped in irony. It is an ode to joy but there is no joy, only a cry of pain reflecting the outrage, the hopelessness of the moment. It is the tormented expression of an orchestra and its conductor saying farewell to a country and a promise they can no longer believe in. Though Furtwangler was eventually exonerated, exhausted and overwhelmed by the weight of memory, unable to protect his reputation in spite of support from many Jewish artists such as Yehudi Menuhin, the greatness that rightfully belonged to him would forever remain elusive.

... View MoreThe true problem with this film is that it locks onto an interesting topic and then squanders it by repeating the same case over and over. It compounds this problem by thinking itself deep. The basic question is whether the conductor deserves to be allowed to continue his work given that he was famous under the Nazis. The answer to that is clearly 'yes' and at no point in the film do they accuse him of doing anything that could be considered a crime. Even if he had been close to Hitler that wouldn't have been a crime unless he did something with it. And it's quite clear he didn't even like the man so what's the point? There is no point at which any of the evidence, or indeed the accusations, have any real bite. His only crime was in not taking a stand against Hitler. How can it be a crime to not get yourself killed? It's just silliness. It seems to be trying to rope all Germans into this question. How could they do nothing to stop this man? Yet it never goes into that question except superficially. The only two characters of any significance are the Major and the musician and both of them represent opposite and boring extremes. Skarsgard comes off the best since his character feels completely noble and pure which puts off the Major only slightly more than it puts off me. He doesn't seem to be a particularly good man, but no law has ever been able to legislate that all people must be good. It is at least an interesting performance. Keitel goes over the top and makes the Major utterly unsympathetic in a boring way. He does nothing but bully people and the only interesting thing about it is how he seems so shocked when people don't think the same way he does. It seems like they were going for an emotion vs. reason, rage vs. acceptance, low-class vs. culture thing, but all the themes are left undeveloped and unexplored. A real shame because the premise shows potential.

... View MoreHere is an arty film of the new millennium. One that reflect upon whatever happened in the last century, and one that in fact deals with the favourite theme of the arty films based on the 20th century: the aftermath of the second world war. It is an interesting period to be talking about, particularly when it deals with such a delicate matter as the inquisitions of the people that were suspects of having been members of the Nazi Party. America on one side, the nation that wants to capture all the Nazis, and Russia, that wants to keep the talented ones. In other words, the country of Germany, stunned by what had been the Nazi period, stunned by whatever they had been kept obscure of, being screwed from both sides.Here is a film where you can't take sides, because the filmmaker takes it for you. Szabo makes it very clear that Dr. Furtwangler is not evil. In fact, this is what we think in Music Box by Costa-Garvas, which is why until the end, we must wonder whether Szabo is playing us, fooling us in actually believing in the kindness of strangers. And on the other side of the good side is the Harvey Keitel side, who makes no gimmicks of the fact that he is playing on the evil, tough side.The outcome is not goofy, it's cheesy. Us being told that we are wrong. Us being told by European filmmakers that Americans were bold. Of course, that is probably true. Perhaps Furtwangler wasn't a buddy of Hitler's. But were the Americans wrong in seeking revenge. under such a dubious and biased ligght, we cannot take sides, when we are not given an opportunity to take sides. Keitel's Maj. Arnold hates the Nazis not because of what they did, but because he is brainwashed. And if that wasn't enough to prove his instability, we get his shakiness when he catches his two associates out on a date, and he is angry at the fact that the woman didn't pick him.The film plays out more like a stage play than a film. In fact, the film is based on a stage play. That wouldn't even be so bad, because Skarsgard is really good at playing the guy we must pity and Keitel is really good as playing the guy we must hate. It's all set out for us. The sides have been picked, we have been cheated. This is another film where the filmmaker manipulates our thoughts, which wouldn't even be so bad. But when the film drags on and is sucked dry of inventiveness as this one, it shouldn't be forgiven. In fact, the only parts where the film flows are the interrogatory scenes, that display Maj. Arnold's rude and aggressive methods that are good at drawing out attention. And Skarsgard is good as the helpless victim.The photography is not perfect, strange, because he decides not to move the camera itself so much, and yet, he doesn't take his time to think through the mise-en-scene. I suppose, however, that you could be doing worse, counting that there is no character in the play that is particularly sexually appealing, which is ever so important on the silver screen.WATCH FOR THE MOMENT - When, after the second time, Skargard's character gets up off his seat. He is angry, scared, defeated. He has no chance is succeeding. That is a brilliant performance. Too bad it's an easy performance, for the rest of the film.

... View More"Taking Sides" powerfully depicts difficult questions most thinking people have had: who is really responsible for genocide? Are all Germans responsible for Nazism? (All Rwandans ... Cambodians ... ? This list could continue forever until we are all in the prisoner's dock.) How is it that highly cultured people, who loved Beethoven, could commit inhuman crimes? Harvey Keitel plays an American officer in post-World-War-Two Germany who is given the job of dealing with Wilhelm Furtwangler, perhaps the best classical music conductor in the world. The question is, can Furtwangler be associated with the crimes of Nazism? Harvey Keitel and Stellan Skarsgaard give equally riveting performances, but Skarsgaard stands out because he depicts a type that films don't often focus on: a man so dedicated to his high art that he comes across as an extraterrestial when confronted with concrete concerns. His performance was certainly Oscar worthy.In a scene as heartwrenching as any I've seen in any film, Furtwangler attempts to present his carefully prepared philosophy of art. To say that he is rudely interrupted is an understatement. I cried for him, and for humanity.Keitel depicts a driven man who wants justice, but who arrived too late to exact it. Nazism's victims are already dead. He can't save them. And, so, he embarks on a Quixotic quest to bring down a man whose relationship to Nazism is questionable.Keitel's character wants desperately for the world to be painted in black and white, with heroes on one side and devils -- a word he uses -- on the other. At a key moment, his secretary, whose WW II family history is pertinent, makes a key disclosure that might have served to widen and deepen his view of the world. But this is a man who does not want a wider or deeper view of the world. He wants justice, something others might call revenge.Moritz Bleibtreu, Birgit Minichmayr and Ulrich Tukur are poignant, heart breaking, and thought provoking in smaller roles.Kudos to Ronald Harwood for his merciless script. Like characters on screen, I often wanted to take a break, to say, "This is just too much." The script falls like a hammer on very difficult issues.

... View More