The plot isn't so bad, but the pace of storytelling is too slow which makes people bored. Certain moments are so obvious and unnecessary for the main plot. I would've fast-forwarded those moments if it was an online streaming. The ending looks like implying a sequel, not sure if this movie will get one

... View MoreIf you're interested in the topic at hand, you should just watch it and judge yourself because the reviews have gone very biased by people that didn't even watch it and just hate (or love) the creator. I liked it, it was well written, narrated, and directed and it was about a topic that interests me.

... View MoreOne of the best movies of the year! Incredible from the beginning to the end.

... View MoreThere's a more than satisfactory amount of boom-boom in the movie's trim running time.

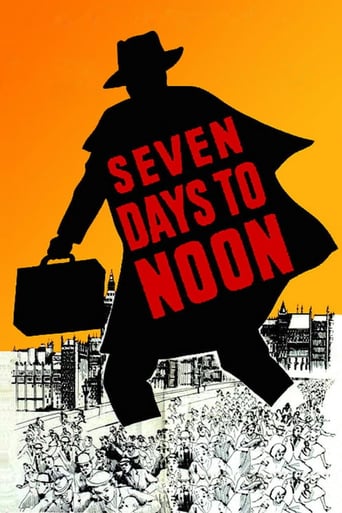

... View MoreMore than one movie was made along the lines of this plot – a scientist decides to turn a deadly weapon against the government or society. I recall at least two others, and each of those lead characters had slightly different reasons. "Seven Days to Noon" may have been the first among the number of films of this nature. But, whether it is or not, this is one tremendous movie. The mystery and intrigue are not something that slowly must be unraveled in this film. They soon become clear. Rather, this movie is made to perfection in the way that it builds suspense and takes the audience along for the ride as Scotland Yard purses the culprit. Will they find Professor Willingdon in time? Will they be able to stop his destruction of a huge area of London radiating (no pun intended) out from the seat of government at Westminster Palace?The plot is superb and one can see why the film won the Oscar for best writing of a motion picture story. But the details of camera work, direction, shooting and other technical aspects are all superb in this film. The acting is top notch as well. The film also shows a well- ordered plan for evacuating London with a few days' notice. In true British stiff upper lip fashion, no one panics. One is tempted to imagine a similar film being made in Los Angeles that likely would show hordes of fleeing, screaming people. This is a very fine movie of suspense, human drama, and detailed police work. The script isn't filled with memorable lines, but I did catch one. Scotland Yard Superintendent Folland (Andre Morell) and the professor's assistant, Stephen Lane (Hugh Cross) are riding in a police car, talking about the professor. Folland says, "Repressing of fear is like trying to hold down the lid of a boiling kettle. Something's got to give eventually."The film also gives a look at some lesser-known but very good performers from early English filmdom. Olive Sloane is very good as Goldie. A younger Joan Hickson is very good as the chain-smoking, nervous landlady, Mrs. Peckett. Audiences everywhere would know her later for her portrayal in many films as Agatha Christie's Miss Marple. And, Ronald Adam plays the prime minister here – a type of role he filled in many of his later films and in TV series. This is a fine first-rate production that most people should enjoy.

... View MoreNot one man, not even one group or organization, should have access to so much power that could destroy an entire city. That is the plot of this early cold war thriller of nuclear power threatened to blow up London by a disillusioned professor. This intense nail-biting clock ticker is just what the doctor ordered to warn audiences of what could happen, and ironically is what has happened. This is terrorism at its scariest before the word "terrorist" was a frequently used word in our vocabulary, because the culprit is threatening to destroy their own countrymen. Sound familiar?Real time photography of Londoners going about their daily tasks is interspersed with the filmed drama, adding much tension to the already frightening theme. The story intersperses the quest to find the bomb and defuse it before its too late, evacuate the entire city (an empty London is a scary looking London!), and the personal dramas of those involved, including the professor's own family.The dramatic structure is aided by an excellent screenplay, crisp photography and an appropriately tense musical score. The cast of excellent British actors seem so natural in their performances that they seem not to be acting, but reacting to the horrors of the story which they are dramatizing. Particularly excellent are Barry Jones as the nervous professor and Joan Hickson as the flirtatious landlady who rents a room to him and becomes an unwilling participant in his quest for mass destruction.

... View More"London can take it!" was the rallying cry in 1940, and a decade later the same, stoic answer to the Blitz might have summed up this tense speculation about the efforts taken to defuse an impending atomic holocaust. The film reflected many real fears of the embryonic nuclear age, but managed to embrace both ends of its argument, with the rogue scientist threatening to explode a bomb in downtown London (unless the government disarms its atomic arsenal) acting as both a voice of conscience and an agent of madness: the message is sane; his method is not. Meeting the crisis with clear heads and stiff upper lips are the real heroes of the film: the civilian and military forces who organize a heroic evacuation not unlike the victorious retreat from Dunkirk. The script benefits from some near-documentary realism and a swift, clockwork plot, earning co-writers Frank Harvey and Frank Boulting (who also co-directed the film with his brother John) an Oscar for their efforts.

... View MoreAn unexpected masterpiece from the Boulting Brothers, "Seven Days to Noon" is an object - lesson in how to make a small - budget suspense movie .It works supremely well as such,but it is rather more than that.The "Atomic Age" was upon us,anti - communist propaganda was coming to a peak and nuclear sabres were being rattled. There was a real fear that World War three might indeed be the war to end all wars and everything else as well.In such a climate a scientist with a conscience might well decide to rattle a few sabres himself in the cause of what he considered the collective good. By threatening to explode a nuclear device in Central London within seven days unless all work on atomic weapons is suspended Mr B.Jones causes a very British panic i.e.things carry on much the same right up until the last moment,an Ealingesque concept if ever there was one. The Boulting Brothers' proposition that the atom bomb was "a bad thing" might seem to belong to the era of duffel coats,beards and open - toed sandals but in fact predates it by several years. Over half a century later it is glaringly obvious to Londoners that any bomb,whether it contains Uranium 235 or fertiliser is a very bad thing and to find one bomber in a big city is a task beyond human capability. By pointing this out to the public in 1950 the Boultings were breaking new ground. Don't watch it through 21st Century eyes then complain that people aren't like that -obviously they're not.But they were then. What you see is the way people behaved,the way they spoke and inter - acted as much as "Eastenders" reflects daily life in London now. People expressed anger,love and hatred without foaming at the mouth. Five years after the end of the war there was still a little of the "Let's all pull together" spirit abroad in the air.Everybody knew what it meant to be British but nobody spoke about it - the polar opposite of today. Although today the Boultings are best remembered for their comedies this little masterpiece from early in their career is a worthy contender for consideration as their finest work.

... View More