The movie turns out to be a little better than the average. Starting from a romantic formula often seen in the cinema, it ends in the most predictable (and somewhat bland) way.

... View MoreThere's a more than satisfactory amount of boom-boom in the movie's trim running time.

... View MoreIt's easily one of the freshest, sharpest and most enjoyable films of this year.

... View MoreActress is magnificent and exudes a hypnotic screen presence in this affecting drama.

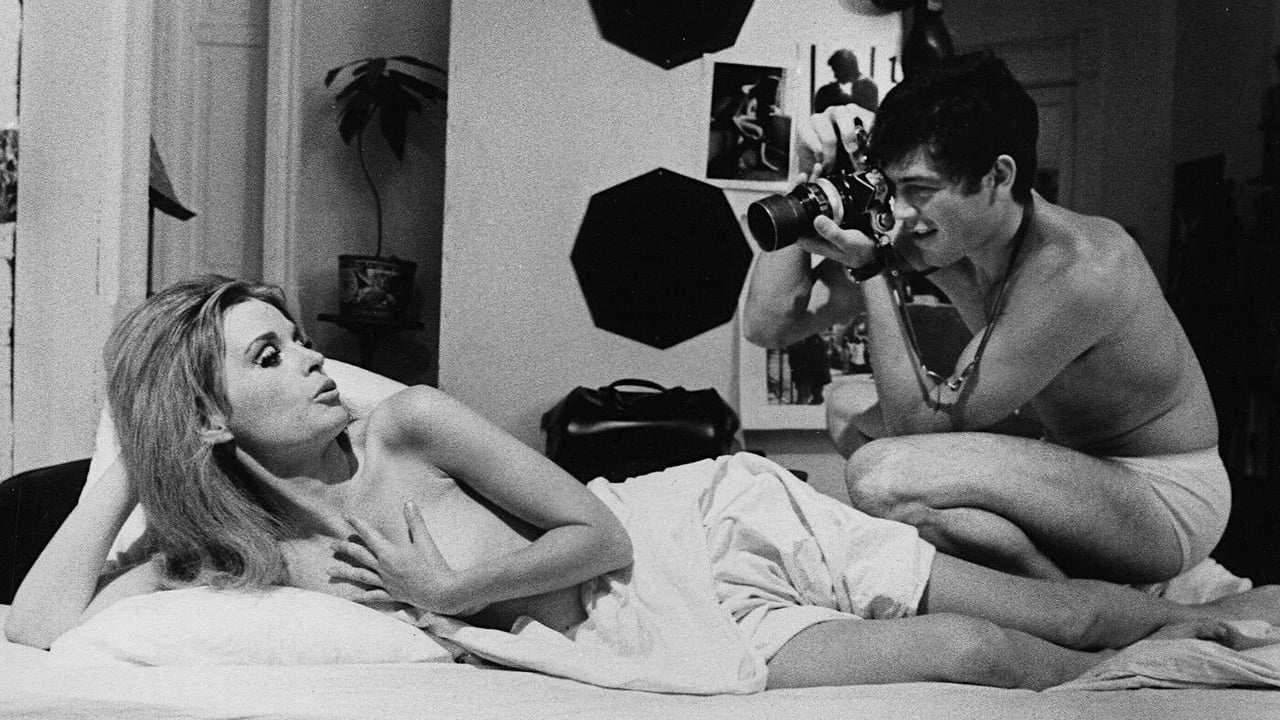

... View MoreJohn Cassellis (Robert Forster) is a TV reporter. This follow his work and personal life. It's a scatter shot of his life and Eileen (Verna Bloom) and her son. It's a semi-documentary where the lines of fiction and reality are often blurred. Sometimes, the only way to tell is the presence of a recognizable actor like Peter Boyle.The film could be very disjointed and experimental. It's diving into the counter culture head first. None of the black activists are willing to discuss anything other than that they don't trust him to do an interview. There is a roller derby match, and a psychedelic Mothers of Invention concert. It is one big jumble.Then it get surreal with Verna Bloom in her bright yellow dress walking among the protesters of the 68 Democratic convention. The riot police are out in full force, and so is the army. I would suggest anybody who find themselves drifting to stay with it to see final section. It is utterly fascinating.

... View MoreA TV news cameraman in Chicago find himself becoming personally involved in the violence that erupts around the 1968 Democratic National Convention.Roger Ebert credited Haskell Wexler with masterfully combining multiple levels of filmmaking to create a film that is "important and absorbing". That is an understatement. This film is great on its own (without the real world footage), but Wexler really lucked out on his choice of subject matter. He was in the right place at the right time to get these kind of shots.What results is not only a film of the highest caliber, but a piece of American history presented in a way that might even be called entertaining. And heck, it has a young Peter Boyle, so you cannot beat that.

... View MoreMEDIUM COOL is one of the most terrifying films ever made.The photography is beautiful, set up by the man who would one day be responsible for the inimitable DAYS OF HEAVEN. The result is visceral. It seems so incredibly "real."But MEDIUM COOL occupies this bizarre, hollow land on the spectrum of cinematic "realism." Realism is an abstraction. Never attainable and, at least in cinema, never wanted. By nature, movies present a clearly fictionalized atmosphere where events, people, and influences from reality are inserted. MEDIUM COOL inverts that system by inserting fictional characters into situations constructed from genuine human anger and fear. As far as cinematic innovation goes, this may be the most dangerous.Wexler is fabricating reality. Our culture is so full of corporations, politicians, and interests trying to construct their own portrait of reality. The movies might be the most famous example of this abstraction. However, MEDIUM COOL's danger exists in its presentation. Wexler was a genius. How he thought he could get away with this film I will never know. He inserts Eileen into the climactic riot, helplessly walking against the tide of police officers, clueless about the issues and only concerned with finding her son. His confidence in such direction points to the horrifying fact that he also believes that history is a malleable material. By inserting a fabrication, a symbol, into tangible human danger, Wexler argues for his ability to alter history. That delusion wouldn't be so dangerous if the material were not presented as a veritable document of late-1960's violence and ethics. The counterargument asserting that all cinema is presented such only strengthens this point -- if all films possess the trappings of realism, MEDIUM COOL attempts to create one anew. Ultimately, the moral argument is murky and Wexler's left-wing fortitude is made silly by the bookending car-wreck. The film turns out to be a self-indulgent autobiography on Wexler, himself. He doesn't try to hide his Godardian influence, but it becomes trite and facile with the final hijacking of LE MEPRIS. His obsession with the power of the camera eventually usurps fringe cultural concerns like Racism, Violence, Political Upheaval, and Feminism. They're all there in MEDIUM COOL, but in the end they only exist because of the camera.Much scholarship is made about Cassellis' responsibility as the hero. So many admire his calm inversion of stereotype. He is the archetypal revolutionary hero. Unmoved and unshaken in the face of tragedy (the opening, for example), he is depicted as someone who lives for the camera. As footage of MLK is shown (who was shot that year), he says "Jesus, I love shooting film." Cassellis is Wexler -- a grounded permutation of "heroic" behavior. But with plenty of faults to balance everything out.Maybe the most interesting question is -- why Wexler? why 1968? why distort filmic tradition now? The answer might be revealed when Wexler films a series of Black adults in the ghetto. They make (somewhat garbled) pleas for Cassellis to get in touch with the "real people." What was the late-60's revolution but a demand for individual attention and the premature glorification of youth? In MEDIUM COOL, Wexler makes an impossible attempt to faithfully represent the little man. This brings us back to the terrifying message of the film.All of this is not to say that MEDIUM COOL doesn't have brilliant sequences. If Wexler wandered around with a camera for a year, I would be fixated. The opening scenes at the security base, the final riot prelude (whenever Eileen was absent), and most scenes with Harold are perfect instructions for cinematic suggestions of reality. The pictures are colorful, focused, and energetic and most of the acting is realized successfully. Indeed, as long as the audience has the capacity to understand the fabrication they are seeing, the photography does enough to resurrect the broken ideology into a formal revolution in itself.MEDIUM COOL is a unique study in cinematic representation. Many passages render and preserve a critical cultural paradigm. One only wishes that Wexler might have actually filmed the events without feeling the need to dress them up.53.7

... View MoreA brilliant film and a seminal one - a product by a major Hollywood studio handled in cinema-verite' style; besides, the various issues it raises - social, political and media-related - have scarcely been treated with such directness and power. The lack of star names in the cast (Peter Boyle, who appears briefly, was not yet established and, even if he had debuted in John Huston's REFLECTIONS IN A GOLDEN EYE [1967], lead Robert Forster's role was originally intended for John Cassavetes) certainly helps sell its inherent documentary feel.Though, understandably, most meaningful to people who witnessed these turbulent times first-hand, and Americans in particular, despite its specific time-setting - Chicago 1968 (partly shot at the actual Democrats convention site, the film proved prophetic because the script involved riots breaking out...which is what actually happened!) - many of its concerns are still very much with us!! Fascinating therefore if slightly overlong - the subplot involving Verna Bloom and Harold Blankenship feels a bit like padding at first (and was actually what remained of a proposed film, with animal interest, about a poor country boy's adjustment to city life!)...but, ultimately, its point is made during the film's latter stages when Bloom goes to look for her missing son - creating an indelible image of a perplexed figure (incongruously dressed in a bright yellow outfit) getting embroiled in all the commotion hitting the streets at that same moment. This, however, results in a goof involving the unexplained presence very early on of Bloom (already wearing the yellow dress but whose introduction proper in the film takes place quite a bit later!) at a cocktail party for members of the press - a sequence intended to immediately precede the riots but which was then pushed forward during editing, so as to deal straight off with the film's major theme of media responsibility! The tragic yet ironic ending - presented as matter-of-factly as any of the news items covered by dispassionate TV cameraman Forster - is very effective.This is certainly renowned cinematographer Wexler's most significant directorial effort; his camera-work (some of it hand-held) is simply incredible, as is Paul Golding's editing (which must have been quite a headache and, in fact, he mentions in the Audio Commentary that several scenes remained on the cutting-room floor; pity they weren't available for inclusion on the Paramount DVD - nor, apparently, were the rights to the 2001 documentary about the film, LOOK OUT HASKELL, IT'S REAL: THE MAKING OF 'MEDIUM COOL'!). Also essential to the unique texture of the film is the fantastic soundtrack (mostly by Mike Bloomfield but also featuring songs by Frank Zappa, among others).

... View More