I love this movie so much

... View MorePurely Joyful Movie!

... View MoreHighly Overrated But Still Good

... View MoreThe best films of this genre always show a path and provide a takeaway for being a better person.

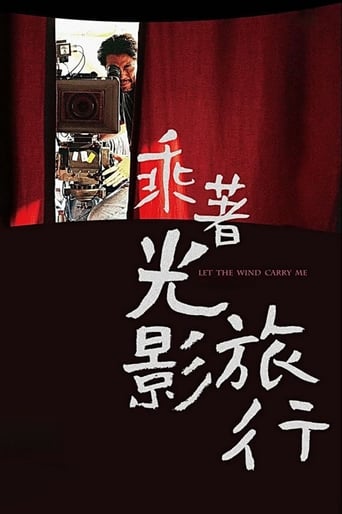

... View MoreThis is a simple, short (88 minutes) documentary on Taiwan's top cultural award winner (2008) Mark Lee, about his career behind the movie camera, his family sentiments and how he influence and help people with his wonderful personality.Perhaps the most significant scene, which comes in the early part of the movie, is on an award presented in Scandinavia for his cinematography work in "In the mood of love". A resident of California and on the road most of the time, he rarely gets a chance to see his 80-year-old mother who lives alone in Taiwan. He took this opportunity to invite her along. In his acceptance speech, he thanked her for raising her four kids while a young widow, sacrificing the best years of her life.His own wife and kids also make sacrifices as he is constantly on the road. This predicament however is not unique to a cameraman but quite common in this day and age. There should be ample empathy in the audience with his loneliness. Underscoring this sentiment is the closing scene when he was in a desolate middle-of-nowhere on a filming project. After a filming sequence, he switched on his cell phone and found 20 missed called and messages. "I was trembling" he told the audience in the award ceremony of the aforementioned top cultural award. "Something terrible must have happened to a loved one" he thought. When he found out that this was about his being given the most prestigious cultural award in Taiwan, his first reaction was not elation but gratitude that nothing bad has happened to his family.The most amazing thing about Lee, as shown in this documentary, is his qualities as a human being. Soft spoken, quiet but not taciturn, Lee is a perfectionist who believes in persistent hard work. He is also a firm believer in turning adversity into opportunity. While examples are abundant in this documentary, most dramatic is in the filming of "The sun also rises", when the crew encountered a snow storm in the desert. While even iron-nerved Jiang Wen was somewhat distressed, Lee was in high spirit and persuaded him that this is a once-in-life-time opportunity: they should film the snow scene and blend it into the story. The result speaks for itself.For a man with such immense strength, Lee is a man of amazingly easy disposition. His charisma is not of the glamorous kind but works quietly. He influences people not by impressing them but rather by winning their trust. Three of today's directors with strongest personality (Jiang Wen, Wong Ka-wai, Hou Hsiao-hsien) unanimously testify in interviews to how Lee influenced and helped them. One interesting episode occurred in his corroboration with Hou, when he wanted to try something that he knew strong-willed Hou would object. So, he worked with his crew in secret-coded language right in front of the strong-willed director. When the result came out, Hou had to admit that he liked it. Interviews with prominent global film personalities from France, Japan, Spain etc all show how well-liked and respect Lee is.Sometimes referred to as "the poet of light and colour", Lee talks a lot about this aspect of filmmaking. Ample illustration has been drawn from a rich collection of iconic films he shot (In the Mood for Love, Flowers of Shanghai, Flight of the Red Balloon, The Sun also Rises, Millennium Mambo and a whole list of others too many to mention). On an intimate plain, we are also shown a "home video" he made on leaves, bringing life to them in a way you have never seen before.

... View MoreKwan Pun-leung and Chiang Hsiu-chiung have made a documentary that celebrates one of the most significant cinematographers today, Mark Lee Ping Bing, who has worked extensively with Hou Hsiao-hsien, Wong Kar- wai, and other great Asian directors like Tran Anh Hung and Hirakazu Koreeda, as well as some European ones. Mark Lee's passion for light and color emerges as rapidly as does his striking appearance. He's a gnarly, beaded, handsome, macho guy but wait... there's something not right, because he's such a workaholic he completely neglects his wife and kids, and only occasionally has done justice to his beautiful, smiling, youthful mother, now 80, who raised him after his father died young. Mark Lee is admired and beloved, but he is a solitary wanderer, perpetually on the road, who when he received notice that he had won his native Taiwan's highest cultural honor, was terrified that the 20 phone messages meant something dire had happened to his family, and kept the great news of his honor when he opened the messages to himself. What kind of man is this? Well, an artist, certainly, maybe a great one, who is as subtle and dedicated as he is open and willing to share his secrets with newcomers to the craft he represents so impressively -- but whose dedication takes its toll on his personal life. We never see Lee's California-based wife at all, and we see his son Jason telling how when as a boy he saw his dad getting an award on TV, he went and turned the set off, because he was angry to be reminded his father was always away. "Now that I'm older I understand better," he says. But this kind of father takes a lifetime to come to terms with. At another time fires endangered his family in California, but Lee knew little about it. Lee is in almost every frame of this film, describing his formation and his passions, and we see images from Hou's A Time to Live and a Time to Die, Goodbye South, Goodbye and Three Times as well as Flowers of Shanghai. Hou's and Lee's battle over the lighting of the latter was a turning point, Lee says. Lee fought to have an enhanced version of candlelight, while Hou wanted scenes simply to be shrouded in darkness. Lee's concern is always to celebrate light in a natural way, but light, not darkness. His sense of nature has a Taoist quality. He goes with the flow (one subtitle actually has him say that) and if it rains when they meant to shoot in sunlight, they must change the scene to rain. If it snows in the desert, they must capture that -- the story behind a striking sequence in Jiang Wen's "The Sun Also Rises,. The movement of leaves in the wind can have a special grace (in Tran Anh Hung's atmospheric and beautiful The Vertical Ray of the Sun). Nature always comes through, Lee says. Somehow things became easier in the ongoing combative relationship between Hou and Lee after Flowers of Shanghai, and they went on to make Millennium Mambo and Flight of the Red Balloon together. There are sequences showing the shooting of Red Balloon in Paris, and a lot of the interview footage was shot there (allowing several French contributors to come in, including Romain Duris, Grégoire Colin, and a French director, scenes of Lee partying with film crews and reminiscing about his early days, and Lee's endless rambling, which entertains, but blurs a sense of the chronology of his career.Director Silvia Chang describes Lee's apprenticeship years in Taiwan as teaching him to be fast and accurate. Wong Kar-wai speaks only briefly, though with great admiration. The word "stability" occurs more than once. It's quality the Chinese crews look for and that Lee supplies. He's solid, reliable, quietly passionate. Wong suggests that if Christopher Doyle, his most famous cinematographer collaborator, is a sailor, Lee is a soldier. There's some focus on In the Mood for Love, particularly the final sequence. Wong says when Lee is given wide open spaces to shoot, he is in his element. This is a documentary drenched in cinematic charisma, but not a technical treatise. The nature of Lee's style as a cinematographer is only suggested by comments and clips. His talk of color and light is fascinating, and we can appreciate what he means when he says he learned emotion from Hou. Unfortunately though there are clips of some of the most known of the 50-odd films Lee has worked on, Variety reviewer Russell Edwards notes that many are not sampled at all, and "the poor quality of some of the clips betrays poor Asian archiving standards and suggests limited access to original prints..." The film arouses mixed emotions. It evokes awe at the Asian cinematic greatness of the Eighties and Nineties to which Lee significantly contributed, but there is doubt about where things are going now, and this seems only a fragment of a larger survey. Edwards concludes: "Lee may have been responsible for some of Asia's best-looking cinema of the past 20 years, but the presentation proves Quentin Tarantino's adage that "the projectionist gets final cut."

... View More