What makes it different from others?

... View MoreJust intense enough to provide a much-needed diversion, just lightweight enough to make you forget about it soon after it’s over. It’s not exactly “good,” per se, but it does what it sets out to do in terms of putting us on edge, which makes it … successful?

... View MoreNot sure how, but this is easily one of the best movies all summer. Multiple levels of funny, never takes itself seriously, super colorful, and creative.

... View MoreWorth seeing just to witness how winsome it is.

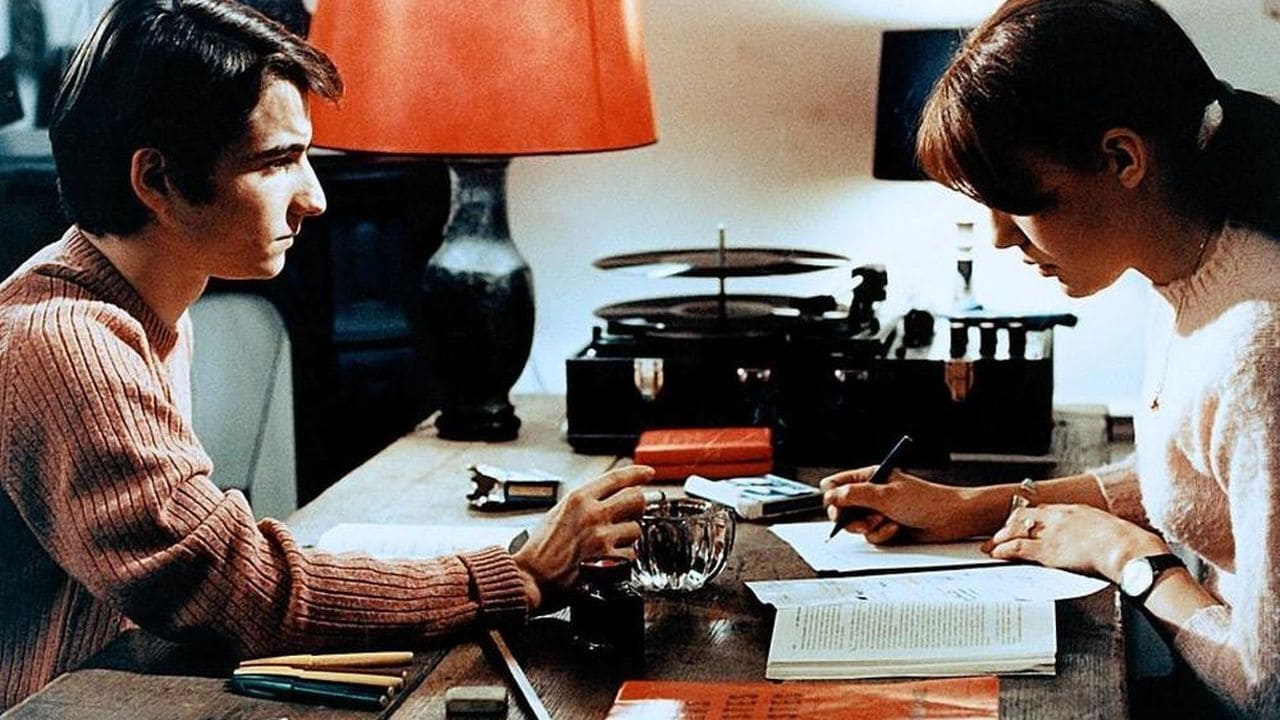

... View MoreGodard's protagonists carry cigarettes in their hand or mouths and are careless roamers, La chinoise is not an exception.Small red books are everywhere. the book shelves are full of it, and the revolutionary students are reading passages out of it. Godard, throughout the film bores audience by reading the passages from these books to convince people that these proverbial sentences are nothing but boresome youth time killer political clichés. Since no one expect Godard to lecture us through a film, the important thing is the overall story. Students are romantising the revolution and politics. The movie contains many references to the then political and ideological events in the world. Godard very frankly and childishly narrate the revolutionary students movements. They are at the end students, living in student quartiers and eating bread and tartiner. This is a film about childish aspect of revolutionary student movements. In the movie there are a lot of scenes that need to be connected..

... View MoreWith Jean-Luc Godard's La Chinoise, I think I'm gonna have to play the historical ignorance card. My knowledge of communism/ Marxism/Leninism and most of the other "-isms" in this particular endeavor as well as my knowledge of the social revolution that occurred in France during the sixties is depressingly limited. Sorry, I'm a westerner victim to a public school education.Godard's La Chinoise is, thus far, his most insufferable endeavor of all his French New Wave films. It's one of the lamest, squarest satires I have yet to see, insufferably telling the same joke (at least I think it's supposed to be funny) of young peoples' devotion to communism and such) over and over, and centering on characters telling having the same conversations over and over again. The film details the relationship between a group of young revolutionaries (Jean-Pierre Léaud, Juliet Berto, and Anne Wiazemsky) in 1960 France that discuss their fondness for the teachings of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, among other key figures that promoted their own ideas, as well as regarding communism with such fascination. Whether we're supposed to marvel at the vapidness of the characters or support them as they anxiously discover and embrace numerous different ways of thinking is beyond me. It seems with every scene Godard wants us to think differently of these characters, and by the end, I have no idea what to take away from the characters or their groggy conversations.Thankfully, we have the use of Raoul Coutard's inimitable cinematography and Godard's fascinating pop-art style to marvel at, making La Chinoise a stimulating visual experience. In a Godard film that often feels repetitive and muddled, the visuals take prominence, and Godard shows his appreciation for bold color as well as pop-art once more with this effort. The whole thing is attractive if, like its characters, feels superficial in the long-run.Having said all that, I can still see how La Chinoise was a daring work for 1967 France. I've already spoke quite a bit about how Godard defied popular cinematic convention, but with La Chinoise and his later, ore political works, he challenged majority viewpoints it seems and became a voice for a generation in many regards. What went from bourgeois, coffee shop/film club banter found a home inside a film, one that defied norms of cinema up until this point. The bright colors, the enthusiastic use of title-cards, and characters showing their appreciation for complex political theory all seemed to connect with mainstream audiences. However, what about people with no background as to this time period? Did Godard think this film would go on to be an oddity for French cinema? What about for those with no idea as to Leftist thinking or the figures the film name-drops so frequently? This is where I play the ignorance card; La Chinoise doesn't provide us with any kind of backstory or precedent to those unsure of the time period. Because of this, it's difficult to catch on if you're just a stray viewer. The only idea I can bring to La Chinoise is it's a clever joke on Godard's behalf to try and gain access to the minds of these Leftist thinkers and get on their side by communicating to them, using "-isms" they'll surely know how to use, while ultimately making fun of them. These are characters that have no idea how political empires or divisions operate, so they stew in their own blissful ignorance (kind of like me in this case), acting as if they have the answers to society's problems by proposing ideology and not thinking twice if it sticks or not.If I'm completely off, excuse my ignorance. Again, just a public school-educated westerner passing by.Starring: Jean-Pierre Léaud, Juliet Berto, and Anne Wiazemsky. Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard.

... View More"Only the guy who isn't rowing has time to rock the boat." - Sartre Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote "Demons" in 1872, a novel about a group of young radicals in pre revolutionary Russia. Based loosely on Dostoevsky's tale, Jean-Luc Godard's "La Chinoise" watches as five young activists spend their summer vacation in a small apartment belonging to "wealthy factory owners who are out of town". Here they study Mao's "Little Red Book", a collection of writings on Chinese communism."La Chinoise's" first two act take place almost entirely within the group's apartment. Red, blues and whites – the colours of the French national flag – dominate. Stacks of Maoist literature line the walls and plastic toys litter the floors. A radio blasts Chinese news reports and occasionally silly Maoist pop songs. We're then introduced to Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Leaud), Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Yvonne, Henri and Kirlov, the only character named after a corresponding character in "Demons". It is implied that Veronique's relatives own the apartment. The kids are all in their late teens and early twenties, some prostitutes, others timid intellectuals, others related to bankers. "I'm ashamed of my wealth," Veronique says."La Chinoise's" aesthetic is now familiar, but back in the 1960s was deemed novel. Told in stylised bursts, this is a confusing amalgamation of agitprop, reality TV, documentary, cartoon, Brecht and conventional fiction. Like most of Godard's films, things only coalesce and take on power with repeated viewings. Godard hoped such a style would "shatter bourgeois aesthetics!", but of course the opposite proved true. Instead of a militant aesthetic (what he called "socialist theatre") which radicalised viewers and instigated change, audiences turned up their noses to what they deemed elitist and incomprehensible.Ironically, the film itself is about "clarity" and "gibberish". "We should replace vague ideas with clear images," one sign reads, whilst another kid states that it is "necessay to bring about the subjective and objective conditions that make revolution possible and render the use of force feasible". In short, they want to overthrow capitalism. The problem? How and what then? "There are different kinds of communism," one kid says, "different shades of red to choose from." Russian Communism, he then points out, does not truly incur the wrath of imperialist America. Chinese Communism, on the other hand, warrants the shelling of Southeast Asia and the escalation of fighting in Vietnam. Surely Maoism is thus "the right way"; a bigger threat to the status quo.This certainty is contested throughout the film. The kids are shown to be narrow-minded, sheltered, annoying, blind to ideological contradictions and nuances, uninterested in anything outside Mao and lost in their own private bubbles. They dream whilst the world spins, treating political ideology as just another pair of goofy consumer sunglasses to be picked up and discarded. On the flip side, these youths are sincere and Godard thoroughly sympathises and even agrees with them; after-all, history is littered with pampered folk like this getting the ball rolling on many human rights issues. Takes time, but still; you can't fight stupid.Godard title is a pun on the phrase "speaking Chinese" (speaking nonsense or gibberish), and also an allusion to "The Italians", a leftist cell beholden to the writings of Antonio Gramsci. Godard's cell, of course, is obsessed with Chinese rather than Italian Communism, they just struggle to morph theory into action. As the film progresses, they also become more militant. "We must suppress undesirable elements that compromise the whole," one morbidly states. Another makes a good point: "revolution costs money but the armies who put them down are free." Guillaume then learns the concept of "struggling on two fronts", which Godard turns into a specific metaphor: the revolution fights itself, its own failings and limitations, as much as the enemy.Veronique, the only character to come from wealth, eventually hatches a plan to both assassinate a visiting Soviet Minister and bomb a university. "Cut off one finger to save ten," her buddies nod like robots, and then: "We must participate in changing reality. Revolutions require terror!". In the film's best scene, Veronique discusses her plans with Francis Jeanson, a real life philosopher who was once arrested for supporting Algerian independence movements (Algeria was once a colony ruled by the French Empire). Jeanson sympathetically stresses nonviolence, seeks to talk Veronique out of her blood-lust, but she doesn't listen. If you're looking to change the rules, why start by abiding by them? Godard's shot composition is ominous: Veronique's hurtling toward history, a history to which Jeanson's back is firmly turned to.The film ends with Veronique's terrorist attacks comically failing. The group then disbands, one member committing suicide, another quitting his job, another emigrating. "Sound and fury scare me," he admits, gobbling down food in a parody of consumerism run amok. As for Guillaume, he's enveloped back into the folds of capitalism, selling fruit and metaphorically assaulted by rotten vegetables. Occasionally he visits the "Year Zero Theatre", in which he symbolically chooses who to free: a plump woman, or a skinny girl, both knocking on an invisible door. Year Zero, of course, alludes to the group's longed for day of victory. "All roads lead to Peking", a sign says, but it's a long walk. "I thought I made a leap forward," Veronique admits, "but it was but a small, timid step on a long march." The group's apartment is then sealed shut, and with it a zeitgeist, Veronique's relatives excavating rooms and unceremoniously dumping Mao's red books. Silly girl, they think. Then came 1968, in which the May day strikes (the Tet Offensive occurred weeks earlier) promptly made a fortune-teller of Godard. Here, over 11 million French workers/students took to the streets, 22 percent of the country striking. France's economy crawled to a halt. This little mini-revolution ended two weeks later, partially betrayed, no less, by the French Communist Party. Henceforth Europe's left-wing became increasingly right. Godard would slip into depression.8.5/10 – See Fassbinder's "Third Generation".

... View MoreIn Japan, La Choise was put on the market as DVD in last year. Although I obtained to view it after some hesitation, the work by Godard in 1967 was brought to very beautiful digitized pictures. About four decades ago, I remembered having seen the poster that was stuck on the wall filled in the graffiti of a political slogan in the movie research club room of an university, although I did not view this work itself. In the poster, Anne Wiazemsky of makeup of Red Guard, wearing the Mao cap and the Mao jacket, hanged up Little Red Book highly with the right hand. The background of the poster was cranberry red. In this movie, the color of white and red is used for symmetry as metaphor. Former suggests bourgeois communism in Western countries, and latter suggests Maoism.A movie starts in the white mansion house in the Paris suburbs. To study Maoism, the five women and men congregate to live a communal life in residence with a white interior and exterior wall that elaborated the intention on the furniture of a bourgeois hobby. We scoped out the setting for Beijing Weekly Report, Mao cap, and much Little Red Book. Those movie property emboss petite bourgeois radicalism. Although Godard was disgusted with the bourgeois Western communism, zeitgeist at the time shared a similar perspective between the young intelligentsia and students having the leftist ideology of Western Europe. The energy in such a spirit of the age was committed to the Maoism, and praised the Cultural Revolution. In Western countries, it was only catastrophe and It is few persons' sacrifice and ended. When on the train Anne Wiazemsky and Professor Francis Jeanson debate the revolution, she sits down toward a direction of movement against the background of the train window, but he sits down conversely. We know the history that the train goes to the destination of violence, destruction, and genocide. Although Godard in those days must have sat down on the same seat of Anne, of course, probably, he must have got off without going to the terminal station. The scene of the conversation in that train suggests ambivalence of Godard himself. In 1968 of the next year when this film-making was done, we encountered The Paris May Revolution. It passed away after febrile delirium. Almost all young intelligentsia and students of those days in the Western countries as well as Godard must have got off. I did so.When about four decades have passed away, we now know The Cultural Revolution in China as a struggle for power at Beijing Zhongnanhai, Vietnam War as a southing to occupy by North Vietnam, a genocide in The Cultural Revolution in China, a genocide by the Pol Pot Administration of Maoism, and also collapse of communism itself. I can now view this movie calmly.

... View More