Good idea lost in the noise

... View MoreAdmirable film.

... View MoreYour blood may run cold, but you now find yourself pinioned to the story.

... View Moreif their story seems completely bonkers, almost like a feverish work of fiction, you ain't heard nothing yet.

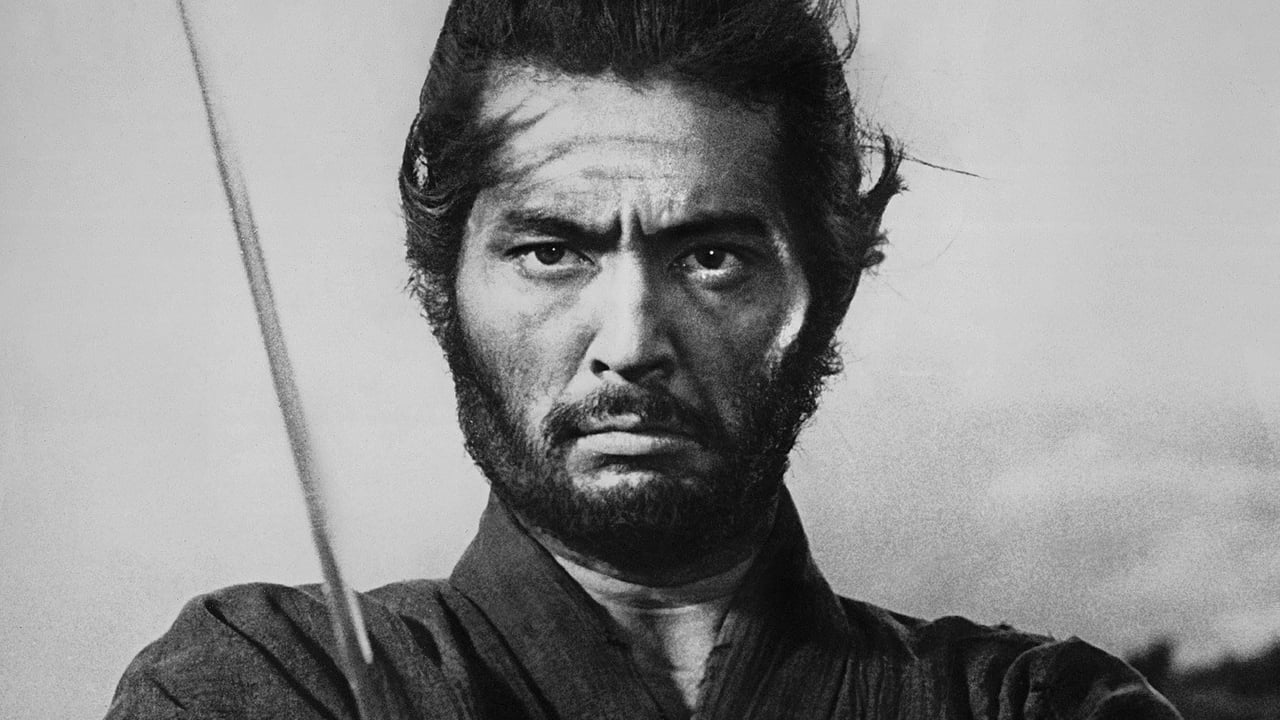

... View MoreUnlike all the Kurosawa films I've seen, this one has a principal protagonist that announces his intention early in the story and then takes the viewer on a stunning journey of revenge that's entirely unexpected. Director Masaki Kobayashi prepares the viewer with a preliminary accounting of the fate of thousands of unemployed Samurai as a result of the 17th Century dissolution of the Japanese Shogunate. Masterless Samurai, or ronin, appear at the doorstep of a feudal lord requesting a place in which to perform ritual suicide, but for the dishonorable, this effort is merely a ploy to accept some small token of monetary value before moving on. "Harakiri" tells the story of two such ronin, and until we learn the true relationship of both men to each other, the viewer is at a loss to understand the real motivation of Hanshiro Tsugumo (Tatsuya Nakadai). With frequent forays into the past utilizing a series of flashbacks, Tsugumo relates the story of his son-in-law, helpless in the face of his wife's deteriorating physical condition and unable to seek medical attention for their sick baby due to lack of resources. What I found quite clever about the story was the absence of the three men Tsugumo called for to be his seconds for the purpose of hara-kiri. One realizes that it can't be simple coincidence that none of these men are available, as the story swerves to a desperate climax that pits Tsugumo against the entire House of Iyi. What would have been a tremendous let down in the story is avoided when Tsugumo follows through on his original mission, unable to physically overpower all the retainers employed by the clan's Master. So many films have the story's hero defeat an overwhelming number of rival opponents that it reduces the credibility factor to zero. At the point Tsugumo knows he can no longer pursue a fight strategy, he takes his life in the ritual manner. For followers of Japanese cinema, this film is a must see, with it's emphasis on honor, loyalty and embracing the truth of one's convictions. Tsugumo's unselfish final act unmasks the hypocrisy of the feudal lord's position, and mocks the cowardice of it's counselor Saito (Rentarô Mikuni). An appropriate amount of swordplay attends the story without becoming excessive, allowing for the more subtle aspects of Tsugumo's strategy to take over the narrative, which it does in compelling fashion.

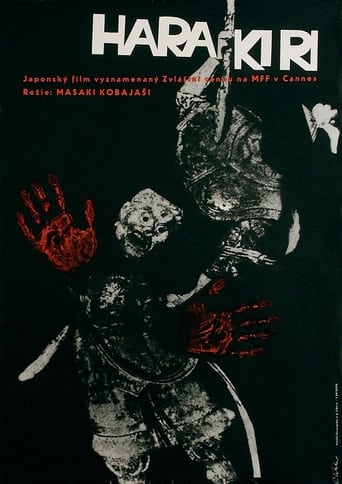

... View MoreKobayashi making a superb Samurai film in the early '60s is like David Vs. Goliath. Kurosawa was on top of his game at this time, and somehow Masaki Kobayashi managed to create a Samurai film on par with the quality of Kurosawa, while staying true to his own style and merit instead of copying what others did before him.The first thing that struck me was that this film, more than 50 years later, still looks fantastic. Especially the great use of high contrast lighting, something you barely see in Japanese productions, set the tone both visually and thematically. The director of photography uses a lot of symmetric shots which look beautiful but tell a story as well. For me the highlight of this film was Motome Chijiiwa's seppuku. This scene was shocking, absurd and also very unpredictable. Excellent editing and cinematography created an unforgettable, yet uncomfortable moment. The turn of events, which slowly unfold as the film progresses is unexpected and will surprise you. But most of all, it will impress you. The director uses some very (without giving too much away) notable techniques to strengthen the effect.Tatsuya Nakadai, one of the greats in Samurai cinema, has some of the most amazing body language you will ever see in movies! I noticed how much work and detail he put into this character by not focusing on his eyes, but rather on his feet - which show that he really is portraying a Samurai. My only flaw is that the beginning of the film, the first twenty minutes or so, does not set the tone which I found to be a bit confusing and off putting.This is one of the greatest films from the golden age of Japanese cinema. It holds up very well and you will walk away very satisfied. If you get the chance, go watch it!

... View More"Who can know the depths of another man's heart?" Hanshuro TsugumoApart from its sheer story-telling gravitas and technical splendour, Kobayashi's Hara-kiri is especially lauded for its plea to look closer, to examine a little more deeply the troubles of those not as fortunate as us. When I watched it for the first time, I was blown away by the arresting wallop of this tension-saturated story's narration , and it was on the second viewing years later that I registered with more delicate acuity, its eloquent entreaty for a more compassionate look at the surface issues of our brethren. Particularly in Japan, the practice of bowing to the larger system and the concept of "honour" being maintained at all costs, looms especially large but of what use is honour if it makes us lose everything dear to us? Hara-kiri takes on the form of a formidable Samurai drama and builds this visceral sentiment with inexorable power, the vise of its narrative swirling and tightening until the physical carnage at the end isn't necessary - the foes have already been annihilated with gentle words. World-class cinematography and flawlessly strong acting further power this monochrome scorcher.Pic opens with a wide-angle black-'n'-white canvas , the neatness and sparse beauty of which is the trademark of director Masaki Kobayashi. Notice how clean these compositions are, whether it is the large ground ouside a chieftan's house, the inner courtyard with its settled pebbles and carefully coiffed platforms for sitting, or even a poor man's wooden house bereft of much conveniences and yet almost spacious in its tidy gestalt. The framing is immaculate when Motome Chijiwa (Akira Ishihama) - a young Samurai struggling for survival - sits with folded knee - in a martial lord's house in front of a tough-jawed warrior who listens to his case. It is 1630 in the Edo region of Japan - peace has been declared in the land but it has devolved into internal war for the highly trained swordsmen called Samurai - they find no employment now, jobs are scarce with workers pouring into any open job-site and Motome is pushed away by a supervisor who cries out that the supervisor will be punished if authorities find out that the formal warrior class is being employed for menial jobs. Motome reports to the House of Li , as other Samurai have done before him, that this utter penury is so dishonourable that he would rather commit Seppuku by disemboweling himself with his own sword in this martial house's courtyard as a final act of honour. The House of Li, manned by fierce-looking superiors, is fed up with this pattern of supposedly suicidal Samurais - they see that many such applicants are willing to accept some money and go away without killing themseles as they initially declared to do. At this stage, Kobayashi racks up the sense of foreboding , panic and icy fear with such elan that the ensuing twenty minutes ranks as one of the most implacable turn of events in black-'n'-white cinema. A few days later, a middle-aged man named Hanshuro Tsugomo (Tatsuya Nakadai), bearded and rather emaciated-looking, shows up at the House of Li with a similar request. He is told the story of Motome Chijiwa as a warning - but Tsugumo, with a wry expression that is beyond gallows humour, calmly states that he will indubitably execute as promised. As great as the previous tightly coiled sequence was, this succeding chapter matches it with its slow burn and unbearable tension which Tsugumo stretches far past breaking point with a story he unspools. Counsellor Saito (Rentaro Mikuni) , heading the house in the absence of the martial lord, is , to put it presisely - driven nuts - by this seemingly interminable narration by the grave-faced Tsugumo but I never got tired of hearing it as the latter lays one dialogue upon another like one revelatory card against the next one till the stakes indicate not just one death but many more. Saito , his strings plucked like a hen stripped to the bone , retreats to the house unable to take more.In other jidaigeki (period-films) like Kurosawa's great "Throne of Blood", the performances though solid do not evoke my specific praise but in Harakiri ,the thespian finesse is on prime display - this could very well have been a starkly lit theater-drama. One can almost feel the cool breeze of happiness coursing through Motome's smiling immensely relieved face after the stifling humidity of despair, alas later , stomach-churning panic sets in to seize his mien. Tsugumo's nominally amused ,mostly dead-serious physiognomy never ever raises its voice but the prosody of his message undulates with the timeless meaning of great scripture. And then there's Saito , more c**t than counsellor, who's so drunk with power and delusions of tough wisdom that his sobriety is nullified by incurable hauteur.I was vastly disappointed by the fight at the end on my first viewing - having brought me to the very peak of expectation, Harakiri's climactic sword-fight seemed not even close to the supremely choreographed ahead-of-its-time bristling magnificence of Daibosatsu toge's finisher. But then as Saito himself says , Tsugumo is a "half-starved" Samurai who's already been through many hells so it is perhaps unfair to expect him to again fight like Japan's greatest champion. The denouement is a sobering indictment of the way history often operates, and the film eventually reclaims its spell-binding emotional and technical territory . To watch Hara-kiri , then , is to acknowledge that even in 1962 when so much of the rest of the world was learning the ropes of top-tier movies, Japan was already capable of engineering peerless cinema.

... View MoreHarakiri is a must see film. A ronin's appearance bears much more significance than it seems at first glance. As his tale unfolds, the tension in the film can be felt as it grows and grows incredibly until it is nearly unbearable. When the tension breaks in the showdowns between our hero and the samurai of the house of Iyi, it is with a vitality that bursts from the screen. The ending is incredible, tying together all the themes in a bloodbath that offers no hope that this will not happen again. The selfish and cruel house of Iyi grows in stature and there seems to be no prospect of betterment for the honourable warriors. The film exposes the bushido code as a farse wherein the honourable are exploited by the selfish. Incredibly shot, written, acted, it is an astounding achievement by director Masaki Kobayashi. Go see it at your next opportunity.

... View More