An absolute waste of money

... View MoreAbsolutely brilliant

... View MoreAmazing worth wacthing. So good. Biased but well made with many good points.

... View MoreStrong acting helps the film overcome an uncertain premise and create characters that hold our attention absolutely.

... View Moreit must see it. for the themes. for the acting. for the messages. a film about fragility of an age. about a struggle. about refuges. about beauty and the need to have it. about solitude, anger, hate, need to escape from yourself. about family. and, sure, about the love. a profound disturbing film who reminds old fears, taboos and vulnerabilities. in fact, a film about the importance of the truth. who could be real useful for understand the life and history from another perspective. in strange manner, a film about happiness. it is the Saint Graal of the lead characters. it is the basic piece for normality. and, in each scene, it is lost. one of films who are more experience than a show. because it represents, after decades, the same challenge.

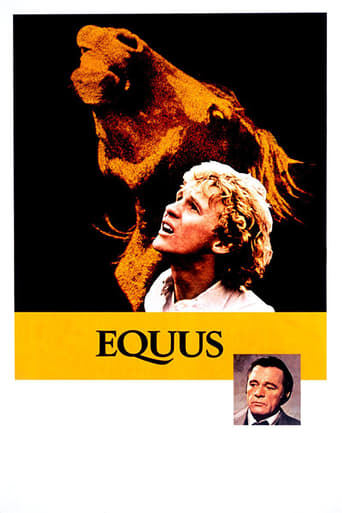

... View Moreone of Richard Burton splendid roles. the convincing performance of Peter Firth. a good play. short, one of movies who remains a web of questions, emotions, stains of feelings because it is a kind of descent in yourself. sure, many critics , result of nostalgia for play adaptation on stage. but it is not a version. only a precise film inspired by the Schaffer universe. the director does an admirable work first for refuse of confrontation with the text. it is a splendid exploration of details and a fight between two manners to discover life. it is a precise construction using few extraordinaries images. a film about lost and axis of life, about values and need to escape from a fake image of world. it is necessary to see it. not only for acting - it is beautiful at whole. not for subject - it could be not new. but for the grace of details. and for the pillars- questions who can give another nuance , for two hours to an ordinary day.

... View MoreThere are many recesses in the mind which begin with a question and extend as far back as the unconscious will allow. Mystery on the other hand begins with a question and usually expects the rational mind to solve it. On a cold night on an English farm, Alan Strang (Peter Firth) a naked youth strokes, plays, rides and makes passionate love to his beloved companion, a beautiful horse. However, instead of a final embrace of love, the youth cries piteously, then blinds him and five other horses. The police are summoned, the youth is arrested, charged, found guilty and then the court must decide what to do with the very troubled boy. The presiding judge decides a mental evaluation is necessary to discover the lad's destructive behavior. Enter Doctor Dysart (Richard Burton) a specialist who begins to identify with the boy's search for understanding, passion and love. While the unfolding mystery begins to illuminate the reason why the boy killed his lover, the doctor also realizes in order to 'cure' him and make him 'Normal' he must eviscerate him into an adult with almost no hope of ever loving anyone without suffering the consequences of reality. A reality which includes his opinionated, inwardly-timid father (Colin Blakely), religious overbearing mother (Joan Plowright) and Jill Mason (Jenny Agutter) with whom he has an affair with in front of his God. The film is a monument of true art and was praised on Broadway and then later in this film. Both Burton and Peter Firth received acclaim, praise and many accolades for their superior performances. The story was written by Peter Shaffer, directed by Sidney Lumet and is considered a Classic on both stage and screen. *****

... View MoreThis is the predictable over-the-top dramatic tosh that they dished up in the early heyday of Larry's 'National Theatre', when the all-male literati still ruled London. It's loaded with all the required themes: paganism, devil worship, bestiality, Biblical delusions and psychiatry, but what it's really about is why men hate and fear a naked, willing woman, something that the production itself reinforces. A far more interesting topic, IMO, would be how women put up with screwed-up men like Alan Strang (Firth). But that would never do, would it. It's a man's world, and it's Strang who is "feeling pain", not Jill Mason (Agutter), the woman he treated brutally, before deflecting his impotent rage on to his kinky hang-up: horses. And a brilliant doctor has been persuaded to treat Strang, not Mason, who surely requires post-traumatic stress therapy. Author Shaffer cleverly introduces an ironical second layer of plot when shrink Dr Dysart (Burton) reveals that he is jealous of the madman Strang, who may be barmy, but at least he has "known passion", unlike the prosaic doctor. Probably only a cabal of gays could come up with such utter rubbish and win glittering prizes for it. But that was a generation ago, and Equus has slipped into well-deserved obscurity since then.

... View More