What makes it different from others?

... View MoreThis is How Movies Should Be Made

... View MoreThe story, direction, characters, and writing/dialogue is akin to taking a tranquilizer shot to the neck, but everything else was so well done.

... View MoreThe movie really just wants to entertain people.

... View MoreOrson Welles was always good at Shakespeare and second only to Laurence Olivier, and in each Shakespeare he made he made it even better. You can see a very interesting line of maturing development through Macbeth and Othello to Falstaff, the final masterpiece - not even Laurence Olivier could make Shakespeare this good. And yet it has its minor flaws.My greatest pleasure and enjoyment, as I saw it now for the third time since the 60s, is above all the marvelous film and picture composition. Every scene could be seen as pictorially a masterpiece of its own. Orson Welles has created his film with an enormous load of experience from experimental cinematography through 30 years, and he seems to have learned everything. Usually in Shakespeare films there are long moments of doldrums but not here - the tempo is exceedingly efficient all the way, even in the calmer scenes. The virtuoso peak is of course the battle scenes in the middle of the film, comparable with Sergei Bondarchuk's overwhelmingness but here made more realistic and convincing in black and white. The mud is really muddy. It's also the point of the film's musical climax - here the music plays an important part of its own.The actors are also perfect every one, but here we come to the one minor detail. The diction is extremely important in Shakespare, the language is all, and if you muddle it all is lost. The best actor here is John Gielgud, who really understands his Shakespeare and makes him right, while the most difficult to understand is actually Orson Welles. His Falstaff is a little too bulky and fat, and his voice is many times lost in the flesh.Another wonderful thing, which gladdened me enormously, is the absolute faithfulness to realism. Welles has really tried to recreate medieval England, especially in the tavern scenes and above all the last one - you can really see how he enjoyed filming it. This faithfulness to style and realism makes the film outstanding in a way almost transcending all other Shakespeare films. Kenneth Branagh wallowed in transforming Shakespeare into any time, age and circumstance including the first world war, many others did even worse, while only Laurence Olivier was equally faithful to realism and style.In brief, it's a perfect film, and its minor flaws you easily forgive for its massive deserts. Only ten points is possible.

... View MoreIt's not exactly daring to declare Citizen Kane to be Orson Welles's most groundbreaking and influential movie. That does not, however, mean that Kane is necessarily Welles's most entertaining and satisfying film. I have long held the latter to be Touch of Evil, but now that I have seen the long unavailable Chimes at Midnight, I might have to reconsider. Welles is indisputably the primary creative force behind Kane and Touch. With Chimes he had some pretty decent source material with which to start. The script is composed of scenes from Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor, Henry IV Parts 1 & 2, and Henry V reconfigured to make Falstaff, Shakespeare's most famous supporting character, into the primary figure of the narrative. But this creates an entirely original story with entirely different themes and politics than those of the original works. This is one of the most contemporary feeling Shakespeare films ever made, even though it in no way departs from the plays' medieval settings. Indeed, the magnificent art direction subtly but powerfully conveys a world of spectacular barbarity where even the most sympathetic characters wander an earth littered with tortured, mutilated, broken bodies displaying not a trace of emotion. There is so much understandable attention paid to Welles the director that we sometimes overlook what a truly gifted actor the man was. And in that regard, this is his masterpiece, the performance of his life . His Falstaff is a soulful hedonist whose gift for gab can make most anyone forgive his rather parasitic nature. This is not the likable, but sometimes violent criminal the character is sometimes imagined to be, but a man who wants his stories to amuse and make one forget or overlook the characters intense vulnerability, and indeed cowardice. Welles always conveys vulnerability, even in his least sympathetic characters, but this is a spectacularly moving performance in which the old Welles uses his physical awkwardness, his jarring girth, to manifest a man who tries to entertain a world he cannot change, or even nimbly navigate. Falstaff is a moving character as written in Shakespeare's three plays that feature Henry V. Yet those plays are ultimately, necessarily, celebrations of feudal power and conquest. The young Henry enjoys the rapscalrony of Falstaff's company, but when the time comes to assume power, he dutifully puts aside childish things and starts a war of conquest for the glory of the nation, which is to say the Crown. Falstaff is, in these plays, that which must be repudiated for the sake of glory. Nothing in this twentieth century work makes feudal power seem glorious. When Henry turns his back on Falstaff it seems the victory of conformity over comradery, of obligation over empathy. It goes without saying that the film is visually sumptuous, characterized by the brilliant deep-focus and chiaroscuro lighting that are Welles's visual hall mark. But one scene stands out as one of the aesthetically greatest of his career as a director. Falstaff, ostensibly a knight, is fitted with a ludicrous, almost tank sized suit of armor to try to contain his rotund form. This machine of awkwardness is plunged into a brutal battle, equipped only for impotence. The image almost had to have been inspired by Max Ernst's near identical 1921 painting, The Elephant Celebes. But where as Ernst's round robot is terrifying, Welles's knight is the clown prince of all that is human.

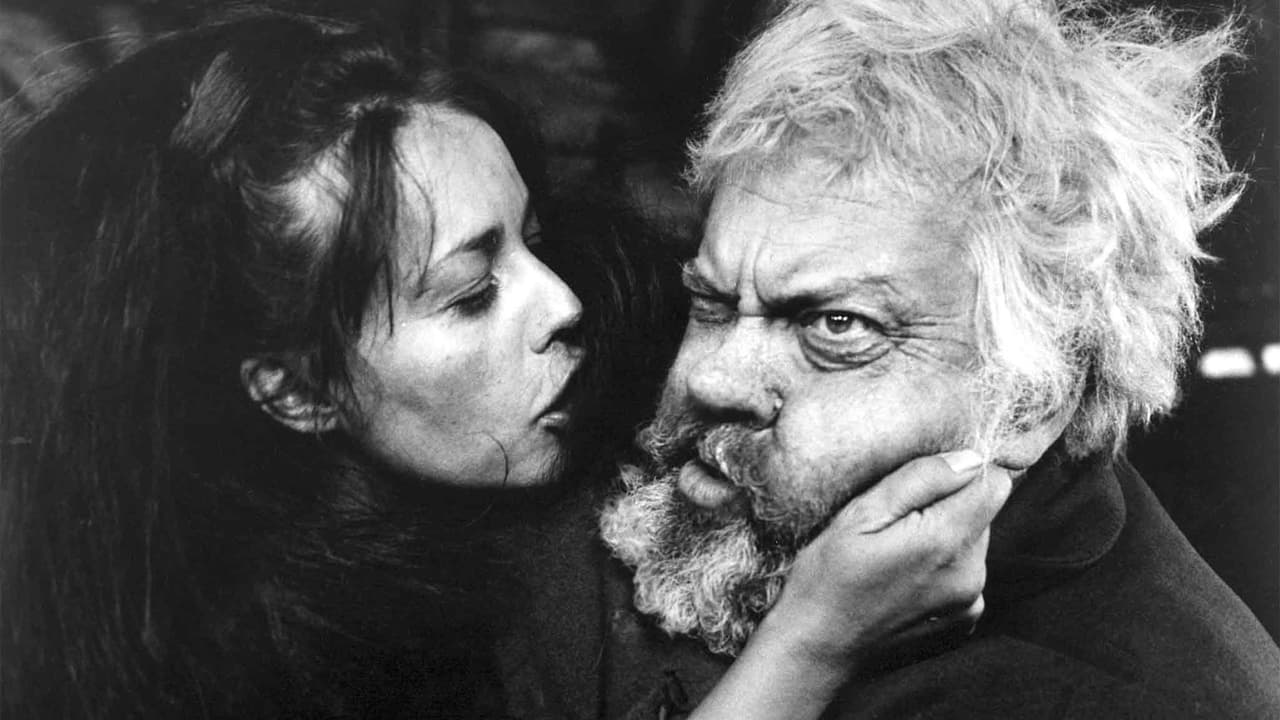

... View MoreOrson Welles appears in this film larger than ever (ironically, according to the IMDb trivia, he had to slim down to play the role - perhaps there was extra padding, one can only assume). He has the build of a boulder, and the face of the character Hagrid from Harry Potter aged in his 70's. Welles was in his late 40's, turning 50, by the time he took on the role of Sir John "Jack" Falstaff, the man who held his own court and council during the years of Henry the IV, but was sort of an outsider. He was a fool, a liar, a sweet guy who could get the attention of men and woman far and wide - from stutterers to the likes of women played by Jeanne Moreau - and yet he was never really 'apart' of the kingdom, that stuffy place where Henry (as played by a platitudinal John Gielgud) is in ill-health from the beginning of this story - even as he, along with his son the Prince Hal (later Henry the Fifth) - controlled the kingdom from outside invading influences.I saw the film with someone who didn't really get what many of the characters want or any dimensions to them (outside of Falstaff, who is a force of nature). I can understand it. It's hard to get a handle at times on this story or even some of these characters; some of that, frankly, we can put on the Shakespeare dialog, which is beautiful and beguiling and deep and existential and poetic and, in 21st century times, slippery almost. But for me, the emotional component was always there, and Welles was a Mega-Master of Shakespeare even back in the 1930's (re his productions of Macbeth, Julius Caesar, even the rough draft of this film, Five Kings). So by the time he got to this, rough-hewed as it is, Chimes at Midnight is like his Final Dissertation as a master filmmaker.Can I just take a moment out to talk how great Welles is here? He commands every second on screen. It can be said he hams it up. Can you blame him really, if it falls into that? I read more depth though in nearly every scene; even in those where Jack Falstaff hears people mock him, he takes it in stride, and can give it as good, or better, than he takes. His tongue is so sharp, and his reactions so BIG, that it's easy to read this as campy. But it's a deeply felt performance, with Welles swallowing this character into his solar plexus. He never plays Falstaff as being as regal as, say, Henry IV, or as Hotspur Percy, who is like many a Game of Thrones character (to put it in modern parlance) who just wants that friggin crown and wants it all his own.I think the characters know what they want, or are trying to figure it out far as it goes. If there can be a legitimate criticism it's that Baxter, as Hal/young Henry V, is kind of the weak link among the cast. Albeit this is a cast with Welles, Moreau, Gielgud, Fernando Rey in a small but commanding role as another warrior. But he takes up a lot of screen time, and is best when having to do fierce reaction or passive poise - enjoying the company of Falstaff he's fine but but totally convincing. No matter - when someone like Welles or someone like Gielgud or Rodway as Percy or Rutherford as the Mistress mining the place Falstaff calls his court... it makes the journey much more entertaining. When you have a Shakespeare adaptation, especially one as ambitious and wild as this one, you got to have a cast that can pull out the emotional connections. They're here.And if Welles really pulls out all the stops with his acting - it may even be his dare I say most towering, monolithic work as an actor, with the range going from bawdy comedy and sweet kindness to shattered tragic tones and bewilderment and shock, everything is there - the filmmaking reaches up to it. There is a battle sequence midway through the film as Henry's troops fight oncoming invaders. My God. Just... if you can get a copy of the film, if nothing else that sequence holds up as one of the two or three essential battles on film. There's chaos, there's fast cutting (yet, even with Welles, you always can see what's going on, far as it goes), and yet there's a story going on as Falstaff, who is on the sidelines of the action, tries not to get involved and even plays dead, and Welles is really crafty in cutting back to this. He apparently only had 100 men at a time to work with. He makes it look like triple that - and all the mud and blood that goes with the dirtiness of an epic battle.It's a filmmaker who loves Shakespeare so deeply, yet he connects it with his own life as an artist and doesn't lose that. It may not matter to some, but I liked that this could be a metaphor for not just Welles but anyone on the margins looking in, unable to break through (especially at the end, as Henry V finally reaches the throne). The energy and force of the direction, the acting, the writing, it triumphs over technical flaws - the syncing of dialog in parts, the fact that parts just connect enough, as it did with Othello in the filmmaking - and in a couple of the performances in spurts. It ranks with the major Welles films, and I do hope it gets to DVD soon (I lucked out with a Welles retrospective that kind of had to play it to be complete) so I can revisit it; I have a feeling, with time, it'll deepen like Kane with appreciation for the craft and ideas on display.

... View MoreAs with some of Welles' other later work, I was a little afraid to approach this. The stories of his troubles abounded. He couldn't pay his actors or crew. It took one hundred and ten years to finish the principal photography. Actors died of old age while waiting for the next call. Welles donned the saffron robes of a Buddhist beggar trying to raise money while making merit. A mob with hatchets tried to assassinate him.But the result was actually quite good. There are wince-inducing weaknesses in some respects. I'll get them out of the way. Everybody was dubbed, and sometimes it shows. And they didn't necessarily dub themselves. It's curious to hear Fernando Rey speaking with a perfect British accent; whoever it belonged to should be applauded. And the young rebel Hotspur, who gets robbed of his youth, looks like Sean Bean, while Prince Hal sounds like Roddy McDowell.There's a problem with the direction too. The speakers don't exactly linger over their blank verse and sonnets and tag lines. They talk too fast for perfect comprehension. After all, even without the constraints imposed on the script by the conventions of poetry, Shakespeare was writing just past the cusp of Middle English, when "thee" finally became "you." And the lingo is arcane. Wine is "sack." Some aphoristic gems remain buried. ("He that dies this year is quit for next," the same philosophy I use with a diseased tooth. And "uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.") What I mean is that it's not easy to understand to begin with, and it's even harder when the lines come thick, fast, and loud.That gets the bad stuff out of the way. The images -- in black and white -- are consistently striking and there are long takes. I swear that if some newcomer, some tyro who was unknown, had directed this film he'd be an overnight celebrity. But with Welles, everyone seemed to be waiting for another "Citizen Kane" and it was never forthcoming, partly his own fault. Like some other major talents, Brando, for example, he seemed anxious to throw away his opportunities while blaming The Suits. But the pageantry is gripping, and there are startling and effective shots from floor level.Welles, thoroughly unkempt, bearded and slow, bloated in baritone and belly, seems to be enjoying himself immensely in the role of Sir John Falstaff, who falls from favor with the new young king, the very same kid he used to rob coaches with back in the day. That kid, Keith Baxter as Prince Hal, gets a morbid case of gravitas when he becomes King Henry V. And look what he went and did after that, a war of choice with France.Welles' Falstaff is a comic character but he's still a knight and gets a bit of tender care from some of the other characters. His fictional character was such a hit with the public that Shakespeare went on to build "The Merry Wives of Windsor" around him. (When I was a kid I always wondered who was the Ann Page that the spices were named after in the A & P supermarket.) I don't think anyone will ever equal Welles' bedraggled appearance in this role. It's no surprise that Welles took parts of several plays and stitched them together to make Falstaff the central figure. From his first homemade movie he's been drawn to narratives of powerful men now grown old and lonely. If he'd lived long enough and played ball he might have gotten around to "King Lear." Margaret Rutherford is a fittingly fussy Mistress Quickly; Jeanne Moreau is a young and attractive Doll Tearsheet. She has pretty legs, which I'd never noticed before. John Gielgud lends his rrrrringing theatrical tones to Henry IV. Okay, Gielgud's delivery is theatrical and old fashioned but he gets the lines across smoothly.The battle scene is well staged and edited, better than those in "Cromwell," for example. And they're pretty brutal for their time. Just out of range of all those swinging swords and raining arrows, Welles is able to make fun of himself. In his suit of armor, he's so spherical that he looks like some kind of mammoth plastic child's toy that has been wound up and is able to waddle a few feet before toppling over.I don't know why this isn't better known. It's pretty good.

... View More