This Movie Can Only Be Described With One Word.

... View MoreThe film makes a home in your brain and the only cure is to see it again.

... View MoreBy the time the dramatic fireworks start popping off, each one feels earned.

... View MoreThe storyline feels a little thin and moth-eaten in parts but this sequel is plenty of fun.

... View More"A tale of love and darkness" tells the story of young Amos Oz, living with his parents in the newly-born state of Israel. Under the pressure of war, the new environment and illness, cracks start to show in what seemed to be a happy family life once.Shortly into the movie, you notice that the style of telling the story diverges noticeably from your usual Hollywood film. Everything is a bit more poetic, more though-through and melancholic. This leads to a situation where you don't really notice what is about to unravel until it actually happens. A lot of warmth and humility accompanie this very personal story and make it universal. While some reviewers here mind that there's not a bigger picture evolving from this, I say that exactly this mixture of emotions and happenings is what makes it a bigger picture in the life of a boy.All in all this is a beautiful movie, that tells about misery whitout any anger. It shows how everyone has his own story and how others can just accompany you on this journey.

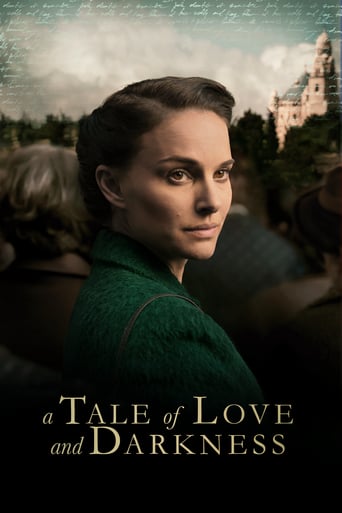

... View MoreScreenwriter/director Natalie Portman's A Tale of Love and Darkness is a brilliantly conceived, masterfully crafted, emotionally powerful, exceptionally thought-provoking work of art. Though Portman's screenplay is based on the memoir by Amos Oz, the resulting film is not just a simple, chronological narrative about the author's life. Instead, Portman has crafted a uniquely cinematic depiction of Oz's attempt to understand his mother's (and to a lesser extent, his father's) psychological state of mind leading up to a crucial event in their lives, in order to explain how it affected his later life. A lessor artist would have been content to simply tell us what happened, but Portman's focus is on helping us understand Oz's beliefs about why it happened, with every scene in the film being a clue to help illuminate his reasoning. To render this complex story of self-analysis in cinematic terms, Portman presents the story from Amos Oz's point of view, using a narrator (portraying Oz at age 63) to guide us through all of the memories he uses as clues to try to understand his parent's actions. But instead of having the narrator explain the relevance of each memory as the film proceeds, Portman challenges us to collect all of the pieces of a complex psychological puzzle so that when the narrator finally explains his conclusion, we are able to duplicate Oz's intellectual process and put the pieces together ourselves, allowing us to understand why Oz chooses to believe what he chooses to believe. Oz's analysis is presented as an intriguing blend of second-hand knowledge of his parents' early life, facts he knows about his parents from first-hand experience (often from spying on them), life-lessons his mother taught him, lessons he learned from real-life experiences, metaphors he discovered in the stories that he and his mother created together for fun, and symbolism he found in the etymology of Hebrew words taught to him by his father. Portman's script manages to weave together all of these different types of clues into an impressionistic pattern that gives the narrator's conclusion a ring of truth once it is revealed. Even so, Portman gives us a lot to think about. For one thing, some of the clues are complicated, requiring the audience to piece together information learned in different scenes. For example, Amos and his mother, Fania, are each bullied by different people in separate scenes, and Portman leaves it up to the audience to compare the ways that Fania and Amos handle the bullying, and to figure out how this helps Amos understand his mother's psychology. As another example, there is a heartbreaking scene that shows what happened during a chance meeting between a young, idealistic Amos and a Palestinian girl prior to the outbreak of war. That scene, combined with the scenes comparing the Jewish people's expectations about the future of Israel to the reality that emerges during and after the war, teaches Oz about a particular aspect of human nature that proves to be a crucial element of his reasoning. Portman also adds depth to this film by including a scene where Fania tells Amos that nobody can truly understand another human being and it is better to accept not knowing than to believe erroneously. This scene adds yet another layer of melancholy to an already gloomy story by implying that no matter how much thought Oz has given this matter nor how well reasoned his conclusion, he knows it is impossible for him (or us) to know whether his conclusion is truly correct. A brilliantly complex, multi-layered script such as this requires a strong director to bring it to life successfully, and in this capacity, Portman proves herself to be a true virtuoso. She and editors Andrew Mondshein and Hervé Schneid create scenes that linger, giving her audiences time to reflect and absorb the content and the beauty of the images. Portman also makes scenes of violence more effective by avoiding the gore and focusing on the human cost. In just a few brief scenes, she manages to convey the truly terrible cost of the birth of Israel, with one of the most gut-wrenching moments in the film occurring with the actor off-camera, and another occurring while we listen to Fania grieving over the loss of a friend. Of course, Portman manages to get excellent performances from all of the actors (including herself), but she also knows how to manage the visual content of a film to enhance her ability to communicate with the audience. She has an eye for composition that makes even scenes of squalor look eerily beautiful, and she knows how to communicate what is most important in each scene. She and cinematographer Slawomir Idziak use a dazzling array of visual techniques to convey the meaning of the story, such as adjusting the color saturation to make the storytelling sequences more vibrant than reality. They also create an intriguing blend of realistic, surrealistic, and symbolic images. For example, during one of the storytelling sequences, they present a stunning image of black birds filling up a white sky to create an image similar to an M.C. Escher lithograph. Another memorable example was a lingering visual of Fania's out-of-focus head that turns and suddenly comes into focus. The script, the acting, and the visual presentation are deftly managed by Portman to create a completely draining emotional experience for the audience. To cap it off, the music by Nicholas Britell is hauntingly effective at conveying the mood of the story. This film is an unusual work of art that should be viewed with an open mind and judged for what it is, not for what you think it should be. If you are excited by the prospect of seeing a well-made, challenging, artistic film that is densely populated with metaphors and symbolism – a complex film that challenges you to try to understand another person's understanding of yet another person's psychology – then this film is an absolute "must see."

... View MoreAmos Oz's memoir of his mother's enlivening imagination, disenchantment and mortal despair is a riveting human drama. But the film's widest import may relate to its backdrop — the emergence of the new state of Israel from the violence of the last days of the British Mandate through the surrounding Arab nations' determined attempt to eliminate her.The two threads share a tragic theme, enunciated toward the end: the inevitable disappointment when a dream is realized. Both for the Oz family and the Jewish people, having a dream enlivens them and gives them the hope and the spirit to continue in the face of terrible experiences. But when the dream comes true it can prove more complicated than expected, even compromised, possibly lost. Amos's father Arieh is a librarian hoping to become a successful novelist. His first novel promises his dream may come true. The smell of the ink is an idea — publication — made material. But the only copies sold are, secretly, to his friend. When the Arabs' attack drives everyone in the building into the Oz flat-turned-bomb shelter, when mother Fania's best friend is killed, when daily life shrinks to fear and scrounging, the family suffers the real consequences of the Israeli dream of statehood. The dream that has sustained the suffering Jews for centuries has come painfully true. When Fania and her extremely privileged family were forced to flee to Israel, she married Arieh, seduced by his words and confident in his ambition. Her marriage dissipates the romance. Her only surviving ardor is her total love of her son. When Arieh comes home in his new National Guard uniform he seems a comic figure, mock heroic. Fania envisions a handsome young man driving a garden stake into the earth, in place of her bespectacled husband. The penetration is personal and political, fertilizing her and the land. He reappears in a flowing tallis amid the desert mountains, enveloping her in a vision both passionate and political. At the end, her ineluctable drive to suicide takes his form as an embracing lover. She kills herself because her romantic dream cannot accommodate her disappointing reality.Arieh adjusts. When Fania turns him away he falls into a relationship with another woman. He lives the bathetic romantic alternative she heroically imagines. He can't understand his wife and the forces that compel her. "She punishes herself only to punish me." He may be the writer but the inspired imagination lies in Fania. Her bedtime stories and life lessons teach Amos to deal with a dangerous reality by telling a story. Fiction sustains the dream even against real enemies, whether the schoolboy thugs who rob and beat him or the Arab nations bent upon another Jewish genocide.Amos grows up as both parents' son, their combination. As a child, he shared his father's love for fresh ink but initially recoiled from the suggestion he might become a writer. He saw the writer unable to help his wife. He'd prefer to be a firefighter or dog poisoner, a curious polarity of helping and killing. He leaves the family to join a kibbutz but he can't escape his mother's legacy, the imagination, the compulsion to tell a story, to sustain a dream. Bronzed like a kibbutznik he remains pale within, the librarian's son, ever more comfortable riding a typewriter rather than a tractor.Novelist Oz is a leading voice on the Israeli left. For all her register as his memory of his treasured mother, Fania's political significance may embody Israel's need to realize that a dream must be inflected and adjusted if its essential values are to be sustained in an unyielding real world. In a tragicomic replay of this theme, both mothers-in-law refuse to accept the marriage. Arieh stolidly sits by when his mother mercilessly snipes at his wife. In the face of Fania's mother's more vicious abuse Fania can only shrink, then release her frustrations and anger — by slapping herself. She hastily repairs to the washroom to hide her tears from Arieh and Amos. Some pains lie beyond the imagination to escape. Both older mothers are yiddische mommas — with fangs.So too the political resonance of Fania's moral lessons to young Amos: "If you have to choose between telling a lie or insulting someone, choose to be generous . It's better to be sensitive than to be honest." This coheres with Arieh's optimism: "You can find hell and also heaven in every room. A little bit of evilness and men to men are hell. A little bit of mercifulness and men to men are heaven."That's the point of the film's single scene of Arab-Jewish community. "Lent" to a childless Jewish couple, little Amos is taken to an important Arab citizen's soiree. In the garden he strikes up a conversation with a little Arab girl. They speak each other's language; there is hope. In his comfort Amos climbs a tree and hangs on the chains of the swing, playing at the Tarzan he has read about and will deploy in his defensive stories. A link breaks, the swing falls, injuring the girl's younger brother. It was an accident, only an accident, but it spreads into an unbridgeable abyss. Amos sees the little girl being severely scolded. For negligence? For befriending the Jew? Any difference between those reasons disappears. Arieh phones to reiterate his apology and regrets, to learn how the little boy is doing, to offer to pay the full costs of the lad's treatment — but is rebuffed. The imagination that can overcome gaps between people can also create them. Oz writes for the Israeli side in this historic cycle of hatred and suspicion. He warns against the possible contamination off their dream with evil and their abiding need for mercy. It will take much mercy if the dream of love is to survive the darkness.

... View MoreThis is a dark, poetic semi-autobiographical movie based on a book by Amos Oz about a young couple and a child who are living through the turbulent foundation of Israel. The movie focuses on hard realities and not the usual pioneer dreams that were sold to the public and which remain part of the myth of that era. It is not an action movie and the movie is in Hebrew, so if you don't like subtitles or have little interest in the Israel's birth or the novels of Amos Oz, you probably won't find this movie as great as I did. However, even if you rate this movie as average, you will still agree that the details are incredibly accurate to the smallest clump of dirt, shirt threat, and stone wall. This is not a cleaned-up Hollywood version of Israel. Natalie Portman's acting is outstanding, the scenes feel real, and the screenplay maintains the story teller's heartfelt artistic touch.

... View More