The Worst Film Ever

... View MoreExcellent, a Must See

... View MoreIn other words,this film is a surreal ride.

... View MoreIt's a good bad... and worth a popcorn matinée. While it's easy to lament what could have been...

... View MoreThe Pleasure Party was made during Claude Chabrol's strongest period, where he made most of his best films. Unfortunately, however, this is a lesser effort from the great man even if it does share some similarities with his best work. It's a marriage drama about a couple who have a conversation one night where the husband admits past infidelities and goes on to actively encourage his faithful wife to pursue other sexual relationships, allowing for them to have an open marriage. This they do but it backfires on him as he gets increasingly jealous of his wife's affairs.The subject of infidelity is one that Chabrol covered many times in his films and here is no different. Similar to other works, the way the characters deal with news of extramarital affairs here is with not much more than a Gallic shrug, which always seems somewhat unrealistic. But then I suspect Chabrol was never purely going for realism and these infidelities were really a springboard to examine other psychological things. I think the single most differentiating factor comparing The Pleasure Party to other similarly themed Chabrol films is that the storyline and central character are very unpleasant indeed. Paul Gégauff, who also wrote this thing based on his own experiences, plays a version of himself and his unfortunate wife is also played by his real wife of the time, Danièle Gégauff. I really hope that this was not really a true representation of himself as the husband character in this one was a real low-life. Interestingly, several years later Gégauff was actually murdered by a later wife, so it does make you wonder I have to say Offsetting the highly unsympathetic central character and unpleasant storyline is a typical Chabrol pastel colour scheme and a classical music soundtrack; both of which contrast quite noticeably with the content of the story. By the end of the film I have to admit wondering just what the message was and who we were being asked to sympathise with. An odd film but not one you would rush back to very quickly.

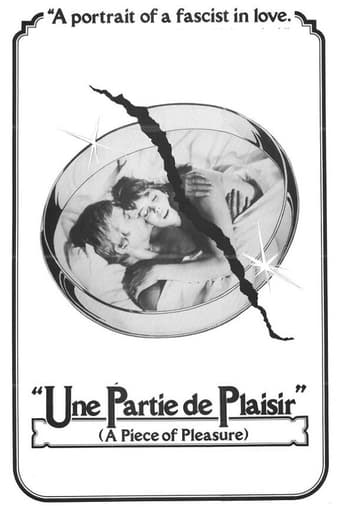

... View MoreIf you look at the picture on IMDb, it's the same one you see on the DVD for this film--a very sexy redhead who is naked. Did you know that this redhead is only in the film for a couple minutes and that you see her naked for only about two seconds?! Yet, this is how the unscrupulous jerks have marketed the film!! Talk about false advertising!! As for the movie itself, I found it to be a real mixed bag--and the bad slightly outweighs the good. While it started off with an interesting premise, as the film progressed it became more and more unpleasant--as well as more and more difficult to believe.The film begins with a couple who seem to be in love. Some time passes and the husband, quite stupidly, tells his wife he's had some affairs and she's free to do so if she wishes--as it won't hurt their strong relationship. However, when she begins to sleep with other men, two things happen--he becomes possessive and jealous and her 'flings' evolve into serious relationships, not just one night stands. Eventually, the two split up and their relationship is over. Now already this is not an especially pleasant film--but it gets MUCH darker and nastier. I'd say more, but, well...I didn't really care at this point.Perhaps the film is saying that affairs are bad or that they are bad if they are serious. Or, perhaps none of these...and it's just a film about a couple of idiots. Regardless, I just didn't care about anyone and the ending was just depressing and unnecessary. Despite director Chabrol's fame, I just wasn't impressed by this film. It seemed superficial, dull and I couldn't have cared less about them.

... View MoreI had to press the return function of the remote control when I believed to hear that Paul Gégauff, main actor and writer of the novel which is the base of Chabrols "Une partie de plaisir", says about his wife: "She sides with Korzybski who claims to refuse Aristote, but she hasn't read either one". I heard right. Although I had mentioned polycontextural logic in a couple of my comments, I would have never expected to find it actually in a film - and here we are.If you reject Aristotelian logic, you give up the whole fundamental of our thinking. With the logical categories of position and negation, also the corresponding ethical categories good and bad are abolished. In such a world everything has to be defined newly, and most things are not anymore either good or bad, but both good and bad or neither one for which a term has still to be invented. I have no idea how Gégauff came to the idea to introduce the founder of General Semantics, Alfred Korzybski, in this movie. However, one could imagine that Korzybski's most important mathematical feature, the "multi-ordinality", is seen here as the metaphysical principle of the open marriage structure of the couple which finally leads into one of the most brutal catastrophes ever seen in a movie. The concept of multi-ordinality replaces unambiguous mappings through ambiguous ones - yet, not in a chaotic, but exactly restricted sense. Possibly, in the eyes of Gégauff's character, his wife breaks out of this restricted area when she goes into a sexual relationship with Habib. Gégauff's character says clearly: "Earlier, she preferred sublime culture, and now she is wallowing in the mud of human scum". (By the way: Also the highly sophisticated language which Gégauff's character uses in order to damn every lower level of human existence into hell, shows a philosophical background which is hard to find anymore.) Thus, his wife crossed the border restricted by the Korzybski-functions and is to be condemned because of that. Up to this moment, Gégauff's character still appears as the guardian of a consistently valid metaphysics; e.g., to his future new wife he underlines many times that he feels freed and relaxed. So, the real breaking-point in the story of this movie is there, where Gégauff himself abandons his own metaphysical principles. From his unreachable position, he comes so-to-say down and turns into a vulgar stalker and beggar who is ashamed about himself. However, the story seems to trespass another border, too, namely the border between Gégauff's character and Gégauff, the writer, himself. In the movie he (almost?) kills his wife on a cemetery, in his real live (just a few years after the movie) he was stabbed to death by his second wife, on Christmas' Eve. Therefore, the final question arises: Does the reflexivity which arises when somebody plays himself still belong to Korzybski's principle or does it violate this principle, because self-reflexivity is excluded in a multi-ordinal world?'- It is.

... View MoreThis may or may not be Chabrol's best, but it must be his bravest. For what else can "The Pleasure Party" (1976) be but an open protest of patriarchy and battery. Think Ibsen's "A Doll House," and you cannot be far off. I think it's the final scenes that erase any minute doubt about the film's intent. First there is the belated rescue attempt of four men and a woman: the adult men's physical prowess seems suspended as if, as men, their hands are tied, while the woman casts a blinding black veil over Philip's head, halting the action, and condemning the actor. And then the prison scene in which Elsie (his new llama or lamb) tells her father that she is unable to learn under the harassment of a male student, to which his non-response includes the same transcendent jargon he used in the cemetery prior to his vicious assault. Chabrol and the Leguaffs have indeed taken their stand with this shattering portrait of male terror--one that explodes out of a convincingly two-faced man, and is thus all the more effective. Yes this is a movie about male power. It is not about sexual impotence, philosophies, or a mid-life crisis , but about Philip's hard-wired connection to masculine identity. If he feels inadequate and helpless in the face of what he can only understand as female weakness, it is because he has bought into women's difference--from men. In other words, Esther is so other to him that anything other than ownership is threatening. The turning point of the film is when he advises Esther --"you should do it."--to sleep with other men. This moment must be as pointedly misogynist as his later acts of violence; for here he equates his lover with sex, temptation, and whoredom --ostensibly to test his purity and his ideas of freedom, but, in effect, he is using her to provoke her own demise. It's very instructive that although he manages the first test--even offering his satiated wife breakfast in bed the next morning, it is sex in bed--with him (to reclaim ownership) must come first. And during a party scene, he argues for the comparison of Gandhi and Hitler--unaware that Gandhi similarly used women to test his own purity, and that the latter's sadistic, eruptive violence would soon adhere to him. What Philip becomes is a full fledged Magus: "the man who tells you everything and what to do" as he explains to Elsie, in his characterizing Habib. Toward Esther, he grows increasingly resentful, suspicious, tense, judgmental, menacing--and possessive. He shows the brawn to break down doors, and a mentality which can accept and enact cruelty. He becomes more withdrawn and, as Esther points out, racist. In the bathroom mirror scene his face, viewed through her tears, is as perverse as the Landru he introduced to his daughter in his House of Wax. The "freedom" he has granted his wife has boomeranged on him. He hates it and everyone and everything connected to it. "Liberty makes me sh_t," he says. When Sylvia simply asks "Why do you yell at Esther?" he answers that she talks too much of freedom and hangs out with guitar players. And his "profound" need for his ex-wife doesn't occur till Sylvia displays her independence in the fishing scene--here he longs for Esther's dependency symbolized for him in her fear of crabs. Esther grasps the picture, but does not have the social power to act sufficiently on it, so finds herself ultimately trapped. However, her defiance is quiet, lucid, and courageous. Her "you, you, it's all about you" refrain, and lines like: "You make the decisions, I only say amen" and "I was great as your reflection" are equal to Ibsen's Nora. But she is more psychologically isolated than Nora, and must suffer from far more abuse, verbal, and, of course, physical. Esther is a battered woman and must endure that syndrome--she cannot fully grasp what Philip says to his buddies: "her weak point move me," and how many times is she willing to forego the depth of her own words: "since when do you care what I say." She can never finally disbelieve her husband--even the forced foot-licking is not proof-- and so, in the end turns to him in a moment of personal crisis because "she is too scared" to visit alone the tomb of the dear deceased aunt, the woman who raised her. The irony here is as devastating as her words are convincing. And her final "NO, NO" has come too late and is heard too late. I understand that the Phillip role was turned down by several leading French actors. If one can relive some of his lines just previous to the assault, one can understand why? But his words serve to finally and totally expose the man behind the mask. His self-assurance, disarming directness, and engaging and almost defenseless smile belong now to a slave-holder, rather than a man who in his words, was "born to be joyful." When he say to Esther that all his sufferings (since their breakup--ha, ha, ha) "must be compensation for what I've been through," the viewer can only say bring on the executioner. It's so extremely tragic that he is the executioner.

... View More